My favourite film/TV/book character crush? Well, this being a Blog devoted to Rudolph Valentino, it’s naturally going to be related to him. But which incredible character out of so many? Perhaps Julio Desnoyers in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921)? The portrayal that catapulted him to fame? Or maybe Juan Gallardo in Blood and Sand (1922)? A performance praised by Charlie Chaplin that was also an invention of Vicente Blasco Ibanez? Maybe one of his two defining representations of a Sheik? In either The Sheik (1921) or The Son of the Sheik (1926)? No. No. No. And no. Surprised? Amazed? Well read on, and all will become clear, in: The Reel Infatuation Blogathon (June 7th to 9th, 2019).

On His Fame Still Lives this October I’ll be posting about A Sainted Devil (1924). Writing about this lost Valentino spectacular, for Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount, has required me to research very deeply. And, naturally, that research involved reading, in its entirety, the basis for the film: the Rex Beach short story Rope’s End. A tale the like of which I’ve never read before; featuring, at its heart, a personality like none I’ve ever encountered. However, before we tackle not just the sensational story, but also the equally sensational protagonist that lives and breathes on the pages, we need to pause, briefly, and see what was going on in the life of Rudolph Valentino.

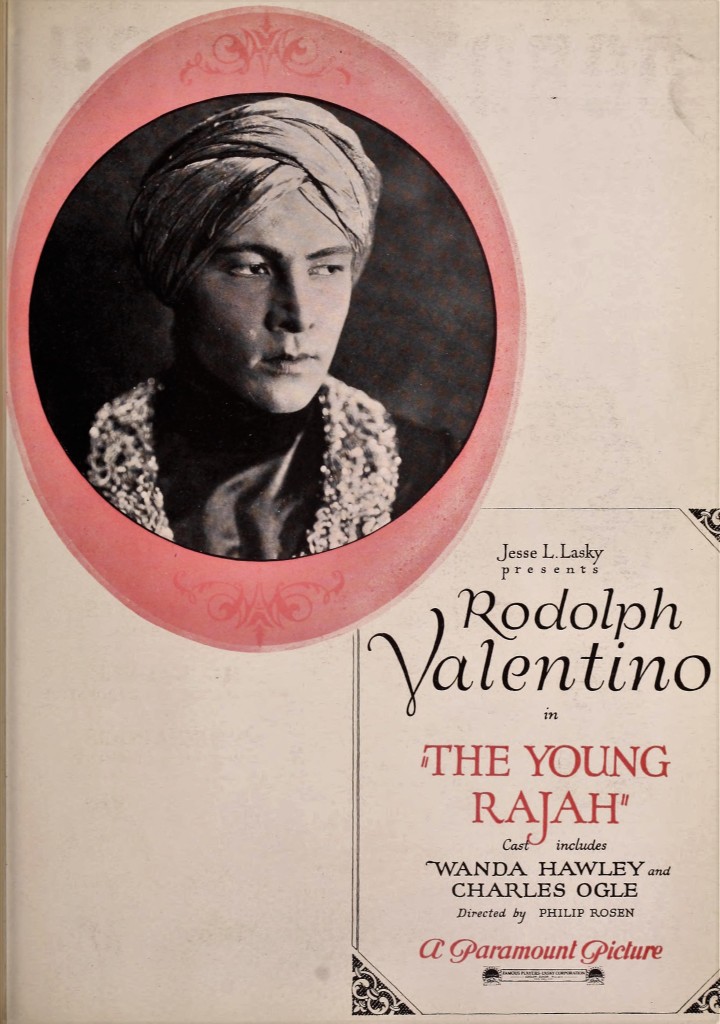

By the Summer of 1921, after less than twelve months, Valentino had moved on from the pre M-G-M Metro Pictures Corp., the studio that had made him a Star, to Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount. At his new studio, where he became a Superstar, in The Sheik (1921), and was then utilised, in quick succession, in Moran of the Lady Letty (1922), Beyond the Rocks (1922), Blood and Sand (1922), and The Young Rajah (1922), he became seriously dissatisfied. His dissatisfaction arising from a combination of: low salary, several broken promises, and a general lack of control and poor material.

What followed was his extended One Man Strike; which lasted a whole year, from 1922 to 1923. A twelve month spell, when, prevented from appearing in any motion picture, he danced his way across the US with his second wife, promoting Mineralava beauty products; published an exercise book and a collection of poems; and even attempted, unsuccessfully, to become a singer. By the Summer of 1923, however, he’d reached a settlement with his employer. And, after a lengthy trip to Europe, followed by another, briefer one, he returned to work at the start of the next year, in an ambitious adaptation of Monsieur Beaucaire. (A short 1900 novel by Booth Tarkington.)

The question of what would follow the expected Smash Hit of Beaucaire – in the end it wasn’t the massive success they thought – wasn’t answered quickly. Much time passed and many possibilities were rejected before the Beach story was settled on. Thanks to Natacha Rambova, his former wife, who, in 1930, published The Truth About Rudolph Valentino, her version of their life together, we know a great deal about the making of what was to become A Sainted Devil. And what we aren’t told by her we can discover from other sources. However, let’s return to the production later, after we’ve enjoyed looking at the inspiration. (Actual text is in bold.)

Beach’s brilliant yarn opens with the following paragraph:

A round moon flooded the thickets with gold and inky shadows. The night was hot, poisonous with the scent of blossoms and of rotting tropic vegetation. It was that breathless, overpowering period between the seasons when the trades were fitful, before the rains had come. From the Caribbean rose the whisper of a dying surf, slower and fainter than the respirations of a sick man; in the north the bearded, wrinkled Haytian hills lifted their scowling faces. They were trackless, mysterious, darker even than the history of the island.

After this great opening, the atmosphere established to the point where we can almost smell it, we now survey the scene. A thatched roof, on four posts, food spread upon a table, and a candle, undisturbed by even a whisper of a breeze, burning quite steadily. Close by another “thatched shed” under which soldiers are gathered ’round a fire. And about, in the “jungle clearing”, huts that have seen better days in which men can be heard talking.

We’re next introduced to the Villain: “Petithomme Laguerre, colonel of tirailleurs, in the army of the Republic…” Seated at the table, in his blue and gold uniform, disappointed with the food he just ate even more than the lack of plunder in the village. He mulls over the day from the comfort of a grass hammock that, like the property, belongs to a Julien Rameau.

We then receive some context:

On three sides of the clearing were thickets of guava and coffee trees, long since gone wild. A ruined wall along the beach road, a pair of bleaching gate-posts, a moldering house foundation, showed that this had once been the site of a considerable estate.

These mute testimonials to the glories of the French occupation are common in Hayti, but since the blacks rose under Toussaint l’Ouverture they have been steadily disappearing; the greedy fingers of the jungle have destroyed them bit by bit; what were once farms and gardens are now thickets and groves; in place of stately houses there are now nothing but miserable hovels. Cities of brick and stone have been replaced by squalid villages of board and corrugated iron, peopled by a shrill-voiced, quarreling race over which, in grim mockery, floats the banner of the Black Republic inscribed with the motto, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.”

Once Hayti was called the “Jewel of the Antilles” and boasted its “Little Paris of the West,” but when the black men rose to power it became a place of evil reputation, a land behind a veil, where all things are possible and most things come to pass. In place of monastery bells there sounds the midnight mutter of voodoo drums; the priest has been succeeded by the “papaloi,” the worship of the Virgin has changed to that of the serpent. Instead of the sacramental bread and wine men drink the blood of the white cock, and, so it is whispered, eat the flesh of “the goat without horns.”

But where is Julien Rameau? Hanging by his wrists from a nearby tamarind tree! Soon Petithomme Laguerre speaks to him. Saying:

“So! Now that Monsieur Rameau has had time to think, perhaps he will speak,” said the colonel.

Yet Rameau’s reply is the same one he’d been giving since the beginning of his torment: that he has no riches. Growing increasingly bored, the colonel tells a subordinate, named Congo, to: “… bring the boy!” And also “a girl”. And we subsequently learn they are man and wife. And that the man is named Floreal.

Congo “and another tirailleur” duly appear with young Floreal Rameau and his equally youthful wife. Both have their hands tied behind their backs. The husband is silent. His wife is in tears.

Now we’re supplied with a good description of the Anti Hero:

Floréal Rameau was a slim mulatto, perhaps twenty years old; his lips were thin and sensitive, his nose prominent, his eyes brilliant and fearless. They gleamed now with all the vindictiveness of a serpent, until that hanging figure in the shadows just outside turned slowly and a straying moonbeam lit the face of his father; then a new expression leaped into them. Floréal’s chin fell, he swayed uncertainly upon his legs.

“Monsieur–what is this?” he asks Colonel Petihomme Laguerre. And then commences a conversation between the Captor and the Captive. The Aggressor wants their money. And the Victim reiterates that there’s none.

When his wife agrees with him Laguerre notices her beauty:

Her arms, bound as they were, threw the outlines of her ripe young bosom into prominent relief and showed her to be round and supple; she was lighter in color even than Floréal. A little scar just below her left eye stood out, dull brown, upon her yellow cheek.

Floreal’s young wife is disgusted by Laguerre, but is forced to reveal her name, which is Pierrine. When he asks her to tell him where their riches are hidden she replies:

“I know nothing,” she stammered. “Floréal speaks the truth, monsieur. What does it mean–all this? We are good people; we harm nobody. Every one here was happy until the–blacks rose. Then there was fighting and–this morning you came. It was terrible! Mamma Cleomélie is dead–the soldiers shot her. Why do you hang Papa Julien?”

Then her young husband becomes hysterical and begs on his knees for mercy. Telling the Colonel to take what they have: “fields, cattle, a schooner”. However their evil Tormentor hasn’t been listening. And, instead, has been eyeing Pierrine. Which makes Floreal even more desperate:

Floréal strained until the rawhide thongs cut into his wrists, his bare, yellow toes gripping the hard earth like the claws of a cat until he seemed about to spring. Once he turned his head, curiously, fearfully, toward his young wife, then his blazing glance swung back to his captor.

Now Floreal Rameau’s worst fears become reality. Despite his attempt to appeal to their Tormentor, Petihomme Laguerre, Laguerre orders orders his men to beat Floreal’s poor father, while he takes the son’s wife into his personal custody, to perhaps suffer a fate worse than death. Floreal Rameau flings himself in front of the Colonel but fails to stop him. And now watches, helplessly as his wife is led away and his father is brutalized:

Floréal shrank away. Retreating until his back was against the table, he clutched its edge with his numb fingers for support. He was young, he had seen little of the ferocious cruelty which characterized his countrymen; this was the first uprising against his color that he had witnessed. Every blow, which seemed directed at his own body, made him suffer until he became almost as senseless as the figure of his father.

His groping fingers finally touched the candle at his back; it was burning low, and the blaze bit at them. With the pain there came a thought, wild, fantastic; he shifted his position slightly until the flame licked at his bonds.

Colonel Laguerre returns to see if the torturing of Julien Rameau is effective. Not noticing that the son, Floreal Rameau, is burning his restraints with the candle on the table. After telling Floreal that he’ll be guarded during the night, and then dealt with the next day, he departs; having: “… an appetite for pleasanter things than this.”

Floreal then cries out to no avail:

“Laguerre! She is my wife–by the Church! My wife.”

Congo and Maximilien, the two subordinates of the Colonel, talk between themselves about the fact that they believe there’s no money. They then decide they’ll kill Floreal’s father, take “the boy back to his prison”, and get some rest. While Congo attends to the old man – who’s not surprisingly expired – Maximilien approaches the son in order to lead him to where he’ll be kept prisoner. Telling him, as he does so, that he’ll be shot tomorrow.

Yet, the desperate, ingenious Floreal, who has by now freed his hands, deftly removes Maximilien’s machete from its sheath. After mortally wounding the unsuspecting owner he then pursues his fellow trooper/’tirailleur’, Congo, who’s head he cracks open, like: “… a green cocoanut, with one stroke.”

Floreal Rameau has time to cut down the body of his dead father but is soon aware that the other men are seeking out their weapons. Thus, as they begin to shoot at him, he quickly disappears into the jungle, as they continue to fire blindly. Laguerre almost fails to subdue them and the first part of the tale ends thus:

The road to the Dominican frontier was rough and wild. All Hayti was aflame; every village was peopled by raging blacks who had risen against their lighter-hued brethren. Among the fugitives who slunk along the winding bridle-paths that once had been roads there was a mulatto youth of scarcely twenty, who carried a machete beneath his arm. In his eyes there was a lurking horror; his wrists were bound with rags torn from his cotton shirt; he spoke but seldom, and when he did it was to curse the name of Petithomme Laguerre.

After the horrifying, blood-soaked opening, Rex Beach tells us what happened to Floreal in the aftermath. How he became resident in the neighbouring country. Gave himself a new name. Learned the language. And became a Seaman. (He had, it seems, been “born of the sea”.) Furthermore:

But he could not bring himself to utterly forsake the island of his birth, for twice a year, when the seasons changed, when the trades died and the hot lands sent their odors reeking through the night, he felt a hungry yearning for Hayti. During these periods of lifeless heat his impulses ran wild; at these times his habits changed and he became violent, nocturnal.

Inocencio Ruiz, as he’s now known, is shunned by women and by men. And people talk of him suspiciously. The suspicious talk is wonderful:

“This Inocencio is a person of uncertain temper. He has a bad eye.”

“Whence did he come?” others inquired. “He is not one of us.”

“From Jamaica, or the Barbadoes, perhaps. He has much evil in him.”

“And yet he makes no enemies.”

“Nor friends.”

“Um-m! A peculiar fellow. A man of passion–one can see it in his face.”

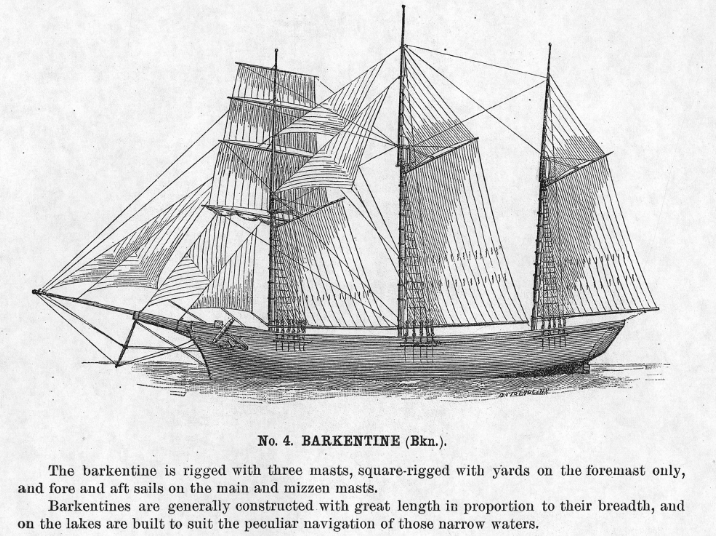

Our Anti Hero’s homeland, Hayti, has, we discover, become peaceful again. And the man that he hates is now ‘General Petithomme Laguerre, Commandant of the Arrondissement of the South’. Inocencio hears of this and departs in a shady Barkentine. He cruises the Caribbean “seeing something of the world and tasting of its wickedness.” After twelve months, at Trinidad, he acquainted himself with a “Portuguese half-breed”, the Captain of a Schooner. Inocencio was eventually promoted to Mate. And then, after a gambling session, won the ship from the “half-breed”.

We’re next in Colon (Panama). During what the author terms ” the French fiasco” of “De Lesseps”. (This information means the story is set in the 1860s and 1870s.) There in “the wickedest, sickest city of the Western Hemisphere”, he:

… heard the echo of tremendous undertakings; there he learned new rascalities, and met men from other lands who were homeless, like himself; there he tasted of the white man’s wickedness, and beheld forms of corruption that were strange to him. The nights were ribald and the days were drear, for fever stalked the streets, but Inocencio was immune, and for the first time he enjoyed himself.

Solitary Inocencio thinks of Hayti and Pierrine. And we’re informed that:

In time the mulatto acquired a reputation and gathered a crew of ruffians over whom he tyrannized. There were women in his camp, too, ‘Bajans, Sant’ Lucians, and wenches from the other isles, but neither they nor their powdered sisters along the back streets of Colon appealed to Inocencio very long, for sooner or later there always came to him the memory of a yellow girl with a scar beneath her eye, and thoughts of her brought pictures of a blue-and-gold negro colonel and an old man hanging by the wrists. Then it was that he felt a slow flame licking at his tendons, and his hatred blazed up so suddenly that the women fled from him, bearing marks of his fingers on their flesh.

Inocencio Ruiz sails for weeks with his Motley Crew. Often visiting the Haytian coast for no reason. He hears gossip about Petithomme Laguerre who has plans one day to be the President. This stirs him to action. And, with the help of “a French clerk in the Canal offices”, he composes an extremely clever letter to His Excellency, General Petihomme Laguerre, Commandant of the Arrondissement of the South, Jacmel, Republic of Hayti. In the communication the Clerk recommends Ruiz. And tells the ambitious Laguerre that there are 200 rifles available at a good price. And that Inocencio is prepared to meet him and discuss the sale.

Antoine Leblanc, the letter writer, expresses doubts about the scheme. But Inocencio Ruiz, the former Floreal Rameau, is adamant. And says, dramatically:

“When I die I shall have no enemies to forgive, for I shall have killed them all,” he said, simply.

We now move to conclusion. Inocencio’s ship, the Stella, arrives at Jacmel, Hayti, and drops anchor. An anchored “Haytian gunboat” worries him, as he hadn’t counted on it being present.

A band was playing in the square, and there were many soldiers. Inocencio did not go ashore. Instead he sent the letter by a member of his crew, a giant ‘Bajan’ whom he trusted, and with it he sent word that he hoped to meet His Excellency, General Laguerre, that evening at a certain drinking-place near the water-front.

We then are told by Beach:

The sailor returned at dusk with news that set his captain’s eyes aglow. Jacmel was alive with troops; there had been a review that very afternoon and the populace had hailed the commandant as President. On all sides there was talk of revolution; the whole south country had enrolled beneath the banner of revolt. The gunboat was Laguerre’s; all Hayti craved a change; the old familiar race cry had been raised and the mulattoes were in terror of another massacre. But the regular troops were badly armed and the perusal of Inocencio’s letter had filled the general with joy.

Captain Ruiz goes to the rendezvous early and sits drinking rum while waiting. (Due to “his threatening eyes” he’s unmolested.) An “older and infinitely prouder” Laguerre finally arrives in a “parrot-green” uniform. “With age and power he had coarsened, but his eyes were still bloodshot and domineering.” They greet each other:

“Captain Ruiz?” he inquired, pausing before the yellow man.

“Your Excellency!” Inocencio rose and saluted.

Ruiz isn’t recognised by Laguerre and a discussion ensues. Eventually the Captain persuades the General to accompany him alone to view the merchandise. They then depart for the Stella:

The moon was round and brilliant as they walked out upon the rotting wharf-all wharves in Hayti are decayed-the night had grown still, and through it came the gentle whisper of the tide, mingled with the babel from the town. Land odors combined with the pungent stench of the harbor in a scent which caused Inocencio’s nostrils to quiver and memory to gnaw at him. He cast a worried look skyward, and in his ungodly soul prayed for wind, for a breeze, for a gentle zephyr which would put his vengeance in his hands.

Inocencio rows the unsuspecting Petihomme out to the Stella:

… as they neared the Stella a breath came out of the open. It was hot, stifling, as if a furnace door had opened, and the yellow man smiled grimly into the night.

The crew of the Stella are amazed to see the General. But their Captain reveals nothing to them of his plan. The ‘Monsieur le General’ is guided towards the cabin. And this is then followed by: “… the sound of a blow, of a heavy fall, then a loud, ferocious cry, and a subdued scuffling, during which the crew stared at one another.”

Afterwards Inocencio emerges and gives orders for them to set sail. A faint breeze means the ship moves slowly, but surely, and Inocencio seats himself upon the deck-house, and drums “his naked heels upon the cabin wall.” Furthermore:

He lit one cigarette after another, and the helmsman saw that he was laughing silently.

Morning comes:

Dawn broke in an explosion of many colors. The sun rushed up out of the sea as if pursued; night fled, and in its place was a blistering day, full grown. The breeze had died, however, and the Stella wallowed in a glassy calm, her sails slatting, her booms creaking, her gear complaining to the drunken roll. The slow swells heeled her first to one side, then to the other, the decks grew burning hot; no faintest ripple stirred the undulating surface of the Caribbean. Afar, the Haytian hills wavered and danced through a veil of heat. The slender topmast described long measured arcs across the sky, like a schoolmaster’s pointer; from its peak the halyards whipped and bellied.

Then:

“Captain!” The ‘Bajan waited for recognition. “Captain!” Inocencio looked up finally. “There–toward Jacmel–there is smoke. See! We have been watching it.”

Their Captain nods. He knows that the ship approaching them is the “Haytian gunboat” that he saw at Jacmel. His crew are uneasy and demand to know who the man is that was brought aboard the night before. When they discover his identity they’re aghast. But Inocencio is unfazed and tells “the Bajan” to locate a new rope, make it: “… fast to the end of this halyard and run it through yonder block.”

Captain Ruiz then returns to General Laguerre in the cabin:

Laguerre was sitting in a chair with his arms and legs securely bound, but he had succeeded in working considerable havoc with the furnishings of the place as well as with his splendid uniform. His lips foamed, his eyes protruded at sight of his captor; a trickle of blood from his scalp lent him a ferocious appearance.

Gradually Inocencio reveals to Petihomme not only who he is but also what his captive’s fate will be. The conversation goes as follows:

“All Hayti could not buy your life, Laguerre!”

Some tone of voice, some haunting familiarity of feature, set the prisoner’s memory to groping blindly. At last he inquired, “Who are you?”

“I am Floréal.”

The name meant nothing. Laguerre’s life was black; many Floréals had figured in it.

“You do not remember me?”

“N-no, and yet—”

“Perhaps you will remember another–a woman. She had a scar, just here.” The speaker laid a tobacco-stained finger upon his left cheek-bone, and Laguerre noticed for the first time that the wrist beneath it was maimed as from a burn. “It was a little scar and it was brown, in the candle-light. She was young and round and her body was soft–” The mulatto’s lean face was suddenly distorted in a horrible grimace which he intended for a smile. “She was my wife, Laguerre, by the Church, and you took her. She died, but she had a child—your child.”

The huge black figure shrank into its green-and-gold panoply, the bloodshot eyes rested upon Inocencio with a look of terrified recognition.

Inocencio Ruiz, now Floreal Rameau once more, further torments his former Tormentor. And then takes him on deck. Petihomme Laguerre is briefly hopeful when he sees the smoke rising from the gunboat in the distance. But before he can finish what he’s saying his Captor slips the new rope around his wrists. Then a dramatic moment:

“Give way!” he ordered.

The crew held back, at which he turned upon them so savagely that they hastened to obey. They put their weight upon the line; Laguerre’s arms were whisked above his head, he felt his feet leave the deck. He was dumb with surprise, choked with rage at this indignity, but he did not understand its significance.

The sailors haul Laguerre higher and higher into the air until: “… his feet had cleared the crosstree.” Then:

“Make fast!” Inocencio ordered.

Laguerre was hanging like a huge plumbob now, and as the schooner heeled to starboard he swung out, farther and farther, until there was nothing beneath him but the glassy sea. He screamed at this, and kicked and capered; the slender topmast sprung to his antics. Then the vessel righted herself, and as she did so the man at the rope’s end began a swift and fearful journey. Not until that instant did his fate become apparent to him, but when he saw what was in store for him he ceased to cry out. He fixed his eyes upon the mast toward which the weight of his body propelled him, he drew himself upward by his arms, he flung out his legs to break the impact. The Stella lifted by the bow and he cleared the spar by a few inches. Onward he rushed, to the pause that marked the limit of his flight to port, then slowly, but with increasing swiftness, he began his return journey. Again he resisted furiously and again his body missed the mast, all but one shoulder, which brushed lightly in passing and served to spin him like a top. The measured slowness of that oscillation added to its horror; with every escape the victim’s strength decreased, his fear grew, and the end approached. It was a game of chance played by the hand of the sea. Under him the deck appeared and disappeared at regular intervals, the rope cut into his wrists, the slim spar sprung to his efforts. In the distance was a charcoal smear which grew blacker.

As Laguerre nears destruction Inocencio counts. Taunts him from below. And reminds him of his past victims. And then:

A cry of horror arose from the crew who had gathered forward, for Petithomme Laguerre, dizzied with spinning, had finally fetched up with a crash against the mast. He ricocheted, the swing of the pendulum became irregular for a time or two, then the roll of the vessel set it going again. Time after time he missed destruction by a hair’s-breadth, while the voice from below gibed at him, then once more there came the sound of a blow, dull, yet loud, and of a character to make the hearers shudder. The victim struggled less violently; he no longer drew his weight upward like a gymnast. But he was a man of great vitality; his bones were heavy and thickly padded with flesh, therefore they broke one by one, and death came to him slowly. The sea played with him maliciously, saving him repeatedly, only to thresh him the harder when it had tired of its sport. It was a long time before the restless Caribbean had reduced him to pulp, a spineless, boneless thing of putty which danced to the spring of the resilient spruce.

Once dead, Laguerre is lowered, and slipped into the still sea. We then have a beautiful sentence:

The sky was glittering, the pitch was oozing from the deck, in the distance the Haytian mountains scowled through the shimmer.

And the story ends thus:

Inocencio turned toward the approaching gunboat, which was very close by now, a rusty, ill-painted, ill-manned tub. Her blunt nose broke the swells into foam, from her peak depended the banner of the Black Republic, symbolic of the motto, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” The captain of the Stella rolled and lit a cigarette, then seated himself upon the cabin roof to wait. And as he waited he drummed with his naked heels and smiled, for he was satisfied.

Reading through Rope’s End, which I’ve obviously abbreviated, without removing vital components, there’s no doubt it was a superb tale. And it’s easy to see why Natacha Rambova and Rudolph Valentino felt it would be an exciting vehicle for him. Featuring, as it does, an exotic central figure, in a foreign, tropical location; plenty of tension, with many opportunities for serious dramatic acting, and emoting; changes of scene and also changes of costume; a cast of interesting supporting characters; and the triumph, if in a dark, very twisted way, of good over evil.

Naturally there were several obstacles to be overcome. It was unthinkable, at that time, due to racial prejudice, that Rudy could portray a ‘Mulatto’. While he’d certainly already embodied a desert Sheik, a coarse Spaniard, and an Indian Prince, each time this had been made acceptable in some way. (Usually by revealing he wasn’t, in fact, completely ethnic.) Also, for the same reasons, there was no way any African American could play opposite him, as a foe. And, lastly, there would need to be an adjustment when it came to the wife that dies. Possibly by showing a happy life before the arrival of the soldiers and giving the audience flashbacks throughout. Or by reuniting them at the conclusion. (In the original she dies giving birth to Petihomme Laguerre’s child.)

In The Truth About Rudolph Valentino, in 1930, Rambova was clear, that before Valentino departed for a short break in Florida, in May 1924, he’d been very happy with the script. According to Natacha, that submitted and approved narrative, was: “… centered about a revolution in South America, full of the color, fire and dramatic situations that had characterized ‘The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’, the plot was motivated by war…”

This all shows, that while Forrest Halsey, who’d already adapted Tarkington’s Beaucaire, had shifted the action from the Caribbean Islands to Latin America, and at the same time most likely dumped the sea going sections, he’d very much preserved the uprising that was the reason Floreal/Inocencio becomes vengeful. What the “color, fire and dramatic situations” exactly were is a mystery. No doubt the adapted character was a wandering, rootless individual (on dry land rather than at sea), that found himself in a series of compromising situations. Natacha Rambova’s mentioning of TFHotA (1921) suggests this.

Having undergone significant, yet satisfactory alteration, it was therefore a shock when the script was further altered during Valentino’s absence. Rambova explains that: “… after the story had been accepted, bought and paid for, the powers behind the throne suddenly decided that for the sake of international policy (or expense) all traces of war must be eliminated. In other words, the very reason for the story, the spinal column of the beast, was amputated. What remained were a few fragmentary incidents strung together by a threadbare plot and given the title ‘A Sainted Devil’.”

Moreover: “I objected loudly to this mutilation of a fine story; it took all of the pep from the picture. I predicted it would be a failure. But my objections were promptly overruled and, rather than cause more trouble, I sank into quiescence. It was the last picture of our contract with Famous Players and we didn’t want more litigation. Anything for peace!”

If we accept her version – I do by-the-way – Rope’s End had gone from being an extremely exciting, if vicious, work, with a simple to understand central character, shifting against a series of visually exciting, exotic backdrops. To a still relatively exciting, perhaps less bloodthirsty storyline, with, again, a simple to understand central character, operating in a colourful, fiery and dramatic world. To, finally, a lacklustre story, devoid of meaning, with a motiveless, certainly unchallenged central character, moving from scene to scene in an environment that was unexceptional.

Personally, with the necessary changes mentioned earlier, I visualise, without difficulty, Rudolph Valentino as Floreal Rameau. I see him as the unworldly, virginal, defiant young Husband. I see him, on his knees, helpless and begging for mercy. I see him transforming and becoming, when given no alternative, instinctive, animal and a murderer. I see him as the forever-changed, lonely unsatisfied drifter; as a fugitive who broods about the past and lives in the moment. I see him as the Master of the Stella with his ugly crewmen. And lastly, I see him, face to face with his wicked adversary, fully prepared to punish him, for the deaths of his mother, and, his father and wife.

It’s a great shame that Famous Players Lasky/Paramount couldn’t or wouldn’t see him as Rameau too. That they made the decision to drastically alter the “accepted, bought and paid for” adaptation. That they put production costs and expediency before great art and good storytelling. That they decided, after all, not to let bygones be bygones. For me, it’s obvious Rudy was denied the opportunity to surpass himself, in The Four Horsemen…, The Sheik and Blood and Sand. Yes, the times were against him, yet that was as nothing compared to having his employers not fully on his side. Immediately afterwards, though they didn’t know it for about another year, the Valentino’s were no longer a Hollywood Power Couple. Backing down over A Sainted Devil (1924), would lead to them being given the run around about The Hooded Falcon, which was never realised. Cobra (1925), which was to follow A Sainted Devil, was Valentino’s second – third in the opinion of some – flop in a row.

The issues that surrounded the adaptation of Rex Beach’s Rope’s End, 95 years ago this year, are of interest to me, and I hope they’ve interested you. If not, at the very least, I’m sure you enjoyed, at least a little, getting to know the story on which it was based. If, like me, you’ve come to appreciate the main character, then my time hasn’t been wasted. It’s possible you may even feel, as I do, that there was a great opportunity for Valentino to excel that he was denied. As explained at the very start I’ll be looking fully at the film A Sainted Devil (1924) this Autumn. Maybe you’ll join me for that? I do hope so! Enjoy the the Reel Infatuation Blogathon, today, tomorrow and Sunday. It’s wonderful to be given the opportunity to be part of it!

Great!!

LikeLike

Wow – this story (pre-studio interference) sounds exciting and drenched in atmosphere. I haven’t seen many of Rudolph Valentino’s movies – actually, just clips – but I think he’d be perfect as the original Rameau.

What a lot of work you’ve done, both researching and abridging the story for us. I never would have come across it otherwise.

As an aside, what are your thoughts on Rambova’s memoirs? Do you recommend?

Thank you for joining the blogathon! It was a treat for you to bring the great Valentino to the party. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so pleased you enjoyed it and that it enlightened you — as you see I post monthly about some facet of Valentino. Michael Morris’s book Madam Valentino is superb and stands the test of time. Get yourself a good second hand copy and prepare to be amazed. If you have access to any good online US newspaper archive, you can view for yourself, her very candid recollections, mentioned in the post: The Truth About Rudolph Valentino (1930). Oh and thank you, once again, for letting me participate. I can’t wait to read everyone else’s contributions!

LikeLike

Oh, my. Thank you for this, Simon. I was entranced by the actual excerpts and by your input about “Rope’s End”! Not only do I want to find this and read it (it’s some of the most beautiful, luscious prose I’ve ever read), but I 100% agree with you and can see Valentino as Floreal Rameau! Knowing that it was him you had in mind while writing this, I could see him even more clearly.

Again, thank you! For your research and passion and for the VERY fascinating account of the behind-the-scenes of it’s making…or should I say it’s ‘not’ making.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And thank you for reading and commenting. More in October. Lots LOTS more. Then I’ll be revealing the entire film scene by scene. Best wishes!

LikeLike

Indeed, the story presented has everything that would be a great role for the right actor, and the right actor was Rudolph Valentino. Thank you for a most illuminating article.

– Caftan Woman

LikeLiked by 1 person

A missed opportunity on all fronts! Thank you for reading and commenting!

LikeLike

Rodolfo Valentino era un grande attore e con questa versione avrebbe mostrato le sue grandi doti. Ti ringrazio Simon per l’accurata descrizione. Sei riuscito a farci immaginare Rodolfo mentre recita questo nuovo copione del film.Grazie per il grande lavoro che svolgi ogni volta.

LikeLiked by 1 person

E grazie per le tue parole gentili e supporto! Cerca più dettagli su A Sainted Devil in ottobre!

LikeLike

What a wonderful post! I love Rudy, too, but your post really provides some fascinating meat on the bone. Loved it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m really pleased you liked it. And saw what I saw, and, what the powers-that-be at FP-L at that time refused to.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this impressively in-depth post. What a treat! I love Valentino, so I am really happy for this piece. Thank you for taking part in the RI Blogathon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And thank you for reading and taking the time to comment. For me Rudolph Valentino is endless fascinating and endlessly faceted. The more I look the more I find — which is quite something when he lived far from a long life. I post about him here once a month. Hope to hear from you again.

LikeLike