In November 1919 Rudolph Valentino married his first wife Jean Acker. It wasn’t, we know, a match made in heaven; and questions continue, to this very day, about what exactly was going on that month. There are questions, too, about what, if anything, was to be gained from the union. Just as there’s curiosity about the aftermath. I hope to answer these queries, in a three part post, titled, not Questions, but Daisy Chained, for reasons that will eventually become clear. As far as I’m aware this is the first deep investigation of this important figure in Rudy’s life.

While Jean may’ve vanished for some length of time, professionally, towards the end of 1915, she didn’t herself disappear. Far from it. In fact, several mentions in the press, in that year and the next, give us some idea of her movements. Her scene or scenes in Are You a Mason? (1915) had to have been completed by late January, for her to be reported about in a light-hearted manner early in February, in The Atlanta Constitution. It seems that Acker had arrived in town at the Hotel Ansley in need of a room. Asking for “the best” accomodation, she was informed, by the Assistant Manager, Charles G. Day, that their finest available was the Bridal Suite. When told it was the most expensive Jean apparently asked: “Has it a tiger skin, or fuzzy rug in it?” When told it did, she said she’d take it, as her $600 Pekingese puppy, ‘Peg’, liked something to play on when he was “lonesome”. The report, titled TAKES BRIDAL SUITE SO “PEG” CAN PLAY ON TIGERSKIN RUG, ended with the statement that she, and Miss Florenze Tempest, who she was there to visit: “… signed up the bridal chamber for a week.” Whether or not the famous Cross-Dresser Tempest, who shared “the bridal chamber” was another early Amour, or simply a Theatrical Buddy, the report, for me, is a wonderful glimpse into the life of Acker in her early twenties. She travels about freely. Behaves like a Star. Has the money for both an expensive pooch – it could’ve been a gift – and the priciest room at a stylish hotel. Has a tongue-in-cheek personality. And is newsworthy where she goes.

One possible reason for Jean Acker’s hiatus, and her travelling, is that she may’ve successfully sued Frank H. Platt for $10,000. Or, been awarded a lesser sum, or secured an out of court settlement. (Platt was the man driving the vehicle which hit Law, Phoner and herself, when they were on Law’s motorcycle, in New York, in the first half of 1913.) According to a report, on January the 6th, 1914, Jean’s damages suit was to be tried that day.)

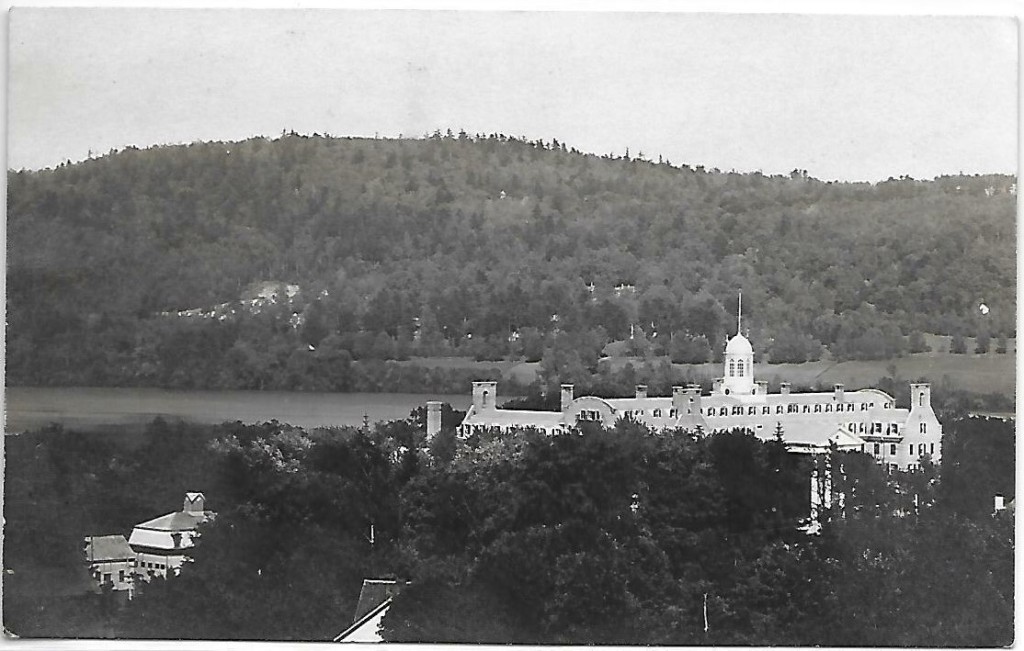

At the start of August, on the 3rd (according to the August 8th edition of Cincinatti’s THE ENQUIRER), she was equally far-flung, when she was very definitely the “guest of honor” at Mrs. William C. Boyle’s “attractively appointed luncheon” at Boyle’s summer home, ‘Cairngorm Farm’, “on the lake shore east”. The Honoured Guest was, the newspaper explained, at the time visiting a Mrs. Charles H. Hopper. Whatever Mrs. Hopper meant to Miss Acker – let’s not draw the conclusion that her attachment to every established, older female, was a sexual or transactional one – they were, a year later, still friends and in one another’s company. Something proven by the paragraph, in a column titled, AT THE OTESAGA, in THE GLIMMERGLASS DAILY, on Monday August, 28th, 1916. As follows:

Mrs. Charles Hopper of Cleveland

and Miss Jean Acker, Mrs. J. R. Pri-

tchard, and Mrs. Asta Ash of New

York, are making a few days stay at

One whole year passes before we see Jean’s name again, when, right at the beginning of June 1917, she’s linked to Mme. Yorksa. Madame Yorska? Yes! That was my reaction too when I first saw the name! Who was she? Very much a subject in her own right, this isn’t really the time and place to delve into her; however, it’s pretty clear she was important to Acker, previous to her meeting the other Madame: Nazimova. A personality who’s now almost totally forgotten, and without even a Wikipedia page, she was, it seems, a rather important dramatic presence in the United States in the Teens. How and when Jean Acker met the Bernhardt-trained Actress fond of playing male parts is a mystery. Yet it’s obvious from a brief look at Yorska’s remarkable career, that Acker had impressed her sufficiently to be included in the cast of Jenny, a play presented on the afternoon of Monday, June 5th, 1917, at The Comedy Theatre, in New York. (THE NEW YORK CLIPPER reveals that the one-off presentation was for the benefit of The Actor’s Fund of America, and that Edmund (or ‘Eddie’) Goulding, later a significant Director, was also one of the performers.)

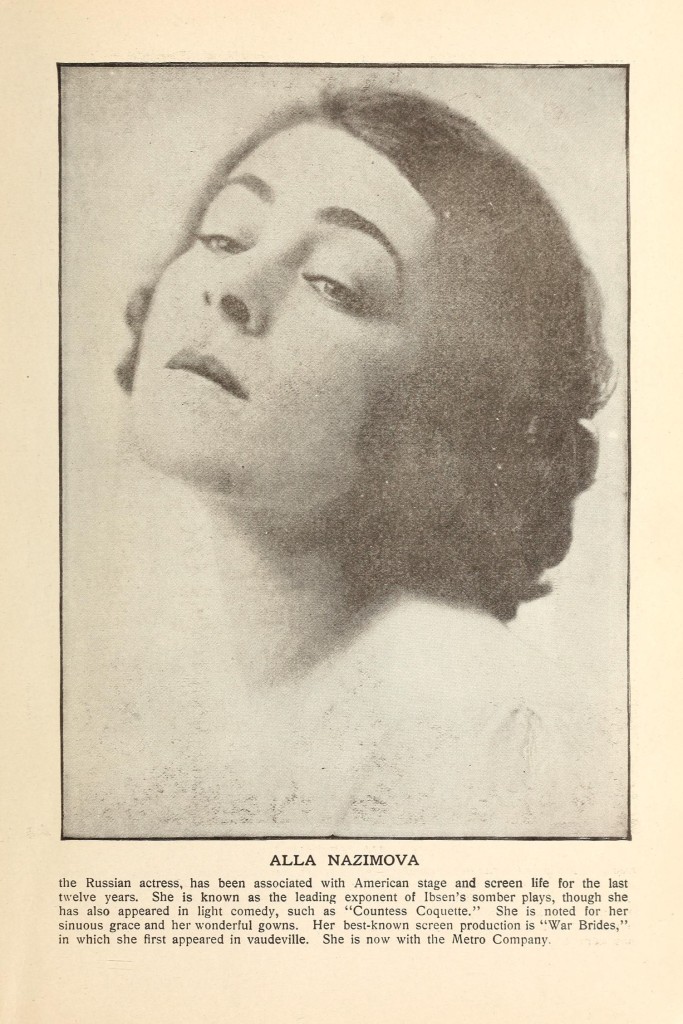

Was it while she orbited Madame Yorska that Acker gravitated, inexorably, to Madame Nazimova? I believe so. (Actually, in the first week of December, in the previous year, Yorska and Nazimova had been two of the “Scores of prominent performers” that had performed at a Blue Cross Fund benefit, at the Hudson Theatre, suggesting they perhaps knew one another.) Alla, the greater Star of the pair, was almost certainly on the East Coast of the United States that Summer, alternately in New York and her home at Port Chester, to the North of the metropolis. Basking in the afterglow of having recently wowed audiences and critics alike – an initial skimpy outfit alone had left them open-mouthed – in H. Austin Adams’ play Ception Shoals between January and May. And readying herself to embark upon a movie career, after the conclusion of negotiations with pre M-G-M Metro Pictures Corp. (Four weeks of tough negotiating, finalised on Friday, July 27th, and announced on the 28th.)

Nazimova, who the Theatre Critic, Charles Darnton, described, in an incredibly detailed review of the first night of Ception Shoals, as: “… an actress of intelligence, feeling and imagination…” was, with much success behind and ahead of her, utterly irresistable that year. Something Harriette Underhill underscored, in December 1917, in her piece titled: Alla Be Praised! Which began:

“One hundred years from now it may

be written in the books which record

historical events that Nazimova was

discovered in 1917…”

Naturally Underhill and her knowing readers were all too aware Madame Nazimova had already enjoyed a decade of stage triumphs — as was Acker. Yet it was in the year the USA entered The Great War she arguably reached her apogee. Harriette Underhill’s declaration that: “Nazimova is more than a person. She is a force.” is telling. And in her responses to the interviewer’s questions Alla’s more telling still. Particularly when she gives her Interrogator her opinion of films and film-making:”… the motion picture is the soul of drama in visible form… It is a triumph—and that’s what we all want, isn’t it?” (A favourite story of mine about Nazimova, Ception Shoals and 1917, that demonstrates the extent to which she was A Force, is the one about how Mrs. Marshall Field and her party were humiliated in a Washington theatre by the Star. It seems that due to comments overheard by her from Field’s box, Madame cried out “Curtain!”, before instructing the Stage Manager to turn out all of the house lights, bar those in the box. (At which, not surprisingly, Field and her friends fled.))

I’m almost certain, due to her later activities, that Alla’s triumph over Jean, her conquest of her, was achieved at this point in time: the Summer of 1917. With nobody alive to ask, and nothing, to my knowledge, ever found in writing, or recorded, we must make bold assumptions about the when, the where and the how. If the when was indeed 1917. And the where was New York. Then we’re left with the how. As already suggested Madame Yorska is one potential link. Yet I favour another candidate, named Herbert Brenon; a man who’d known Acker since 1913, and had successfully directed Nazimova, in her first, one-off motion picture, War Brides (1916). Easy indeed it is, to imagine Jean Acker seeing and saying hello to him at a party, a restaurant, the theatre, or even on the street, while in Alla Nazimova’s company.

I don’t see it as a problem that we wait twelve months to see the two women mentioned together in print. For me, their combination in the same sentence is so casual, it suggests, the unsaid being the clue, that the unknown journalist was aware they weren’t newly acquainted. The quickie marriage of Actor George R. Edeson to Actress Mary Newcomb that following Summer was a minor off-stage drama. The hasty nuptials, which in a way oddly echo Acker’s own, were followed, a report in the New York Tribune reveals, by a dinner at the Hotel des Artists [sic]; at which the guests, including Mme. Nazimova and Miss Jean Acker, were sworn to secrecy as to the place and time of the ceremony, and, the couple’s later whereabouts. Secrecy was, of course, the theme, at least to outsiders, when it came to Alla and Jean. So much so, that at this distance, we know virtually nothing of their very serious and lengthy affair. Yet serious and lengthy it was. And, in time, rather consequential to them both — though they didn’t know it, in 1917 and 1918.

Perusing the relevant pages of Gavin Lambert’s Alla Nazimova biography, Nazimova: A Biography (1997), we learn little about the commencement of their relationship. Just as he’s lacking in detail about Madame’s entry into Filmdom; failing to mention how she’d openly offered her services for $50,000 per production, and publicly floated the idea of working with D. W. Griffith (following his return to the USA from The Western Front), Lambert’s very noncommittal when it comes to any pathway. (A little odd when you consider his general hypothesizing elsewhere.) It’s clear, when we consider the evidence in the New York Tribune, that Nazimova didn’t discover Acker in the September of 1919. Jean had never been known as “Jeanne Mendoza”. Wasn’t 26. Hadn’t, at any time, been “a dancer in vaudeville” or a “small-part actress in summer stock”. And the less said about: “… hardly known to the world at all.” the better. Yet, it would be churlish to suggest that his yet-to-be-surpassed life gives nothing when it comes to Alla and Jean; as it absolutely doesn’t, as will be seen.

It was at the end of 1918, on Friday, December 27th, that industry publication, Wid’s DAILY, reported on the return of Jean Acker to film-making. Small news items, in that month and the next, informed the business that Miss Acker had been engaged to support the popular Fox Film Corp. Star, George Walsh, in a production to be titled Tough Luck Jones. (The title had already altered from Jinx Jones and would end up being Never Say Quit.)

As we don’t know how Acker came to be teamed with Walsh – no report enlightens us – we’re forced to speculate. Her mixing in the right circles and being in New York was probably sufficient for her to cross the path of someone – an Agent, Director or Executive – that facilitated it all. Though it was very much the case that the majority of filming was conducted in the West by this time, business was still being concluded in the East, at the headquarters of the varied, significant studios. And this was obviously beneficial to her when it came to William Fox’s concern. (Fox, seldom, if ever, went to California.)

“It is typically a George Walsh concoc-

tion, a mass of complications furnishing

the star opportunities to display his

physical agility strung upon a story

thread a little stronger than customary.”

From REVIEWS, EXHIBITORS HERALD AND MOTOGRAPHY, March 22nd, 1919 (page 33).

Looking at reviews of Never Say Quit (1919) (a good example, being Hanford C. Judson’s, in the March 29th issue of THE MOVING PICTURE WORLD), we can see how Jean adapted to the times by playing: “… a big-eyed vamp…” Her part, was, it’s true, minor. (She’s billed simply as: Vamp.) And her screentime limited. (Just one scene it appears.) Yet, she was to be featured, prominently, in advertisements. (See above.) And find her portrayal would lead, quite soon, to a better role, in a far, far bigger Fox Film Corp. production. A great part in a wholesome, feel-good film, which would introduce her to more of her country men and country women than ever before.

That the death and burial of her Grandmother and namesake, in February 1919, didn’t derail her, despite it being a blow, is proven by the fact that after she completed work opposite Walsh, Acker signed up for Edward A. Locke’s new play The Dancer. The story of Lola Kerinski, a Russian performer protected by a Manager and a brother, who falls for a wealthy American, who she marries, loses, then reunites with, opened at the Grand theatre, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania on February 13th. VARIETY‘s anonymous reviewer, on the 19th, felt a week or two of rehearsals had been insufficient. “… players were …. [unsure] of their lines…” and “the play” required: “… blue-penciling, speeding up and more vitality.” Despite this, the producers, “The Shuberts”, had: “… staged the play well and surrounded the principals with capable players.” (Jean Acker was one of these.) By the time the cast reached Poli’s theatre, on the 23rd, at the capital city Washington, it flowed nicely. However, on March the 5th, at The Majestic theatre, Providence, Rhode Island, locals objected to the two main characters, the Wife and Husband, kissing in bed and appearing dressed in nightwear, and complained to the relevant authority. Sergeant Richard Gamble, “amusement inspector”, consequently requested serious alterations.

Was bedroom fun on Miss Jean Acker’s mind too? By March she’d found the time to seek out a new home for herself; eventually settling on a sub-let, handled by Pease&Ellman (for Trowbridge Calloway), at 662 Madison Avenue, in New York. To be a block away from Central Park, even in the Spring of 1919, wouldn’t have been cheap. So I wonder if Alla Nazimova was paying for the apartment. And if it was perhaps a place for the couple to rendezvous when Madame was East between films. Of course, being back in business, as she was, Jean might’ve been in a position to rent in a nice part of town. There’s no denying that she’s named as the new Tenant, in the RESIDENTIAL LEASES column, in THE SUN newspaper, on Monday, March 24th. I get the impression, even though it was standard practice at the time, that Jean publicized her move because it suited her for people to know. This was not a publicity-shy individual. Being in the press was enjoyable for her. And she wanted to look good, as people do, when they’re in a profession where looking good’s of the utmost importance.

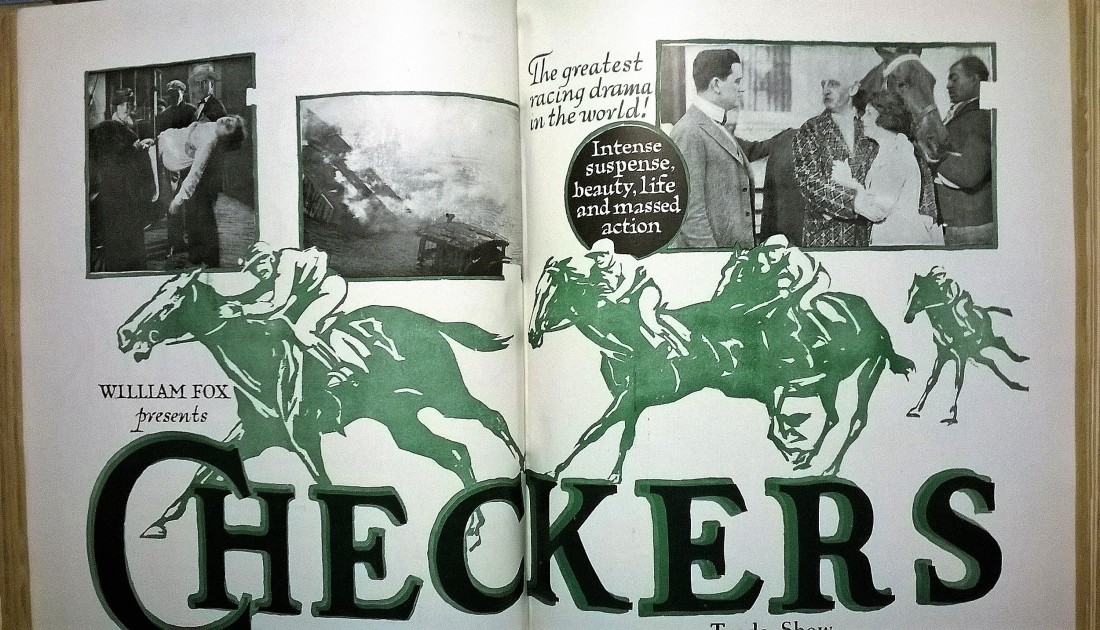

So good did Acker look that Spring, that as soon as the rights were secured (by William Fox) to film Checkers (a late 19th C. novel by Henry M. Blossom Jr. adapted for the stage and much revived), it was announced she was to star opposite Thomas J. Carrigan. With the Director, according to the first publication to announce it (Wid’s DAILY, on Friday, March 7th), to be Richard Stanton.

The picturization of Blossom Jr.’s Checkers was, it must be stated, on a whole different level to Never Say Quit. On March 15th industry title THE MOVING PICTURE WORLD was unequivocal: “One of the biggest casts ever assembled for a motion picture…” was at work. (A cast of “nearly fifty principals”.) And “The racing scenes which helped make the play famous…” were to “… be photographed at one of the southern racetracks.” It was expected, the final sentence revealed, that the adaptation would be released that Spring. And would be: “… a big special feature.”

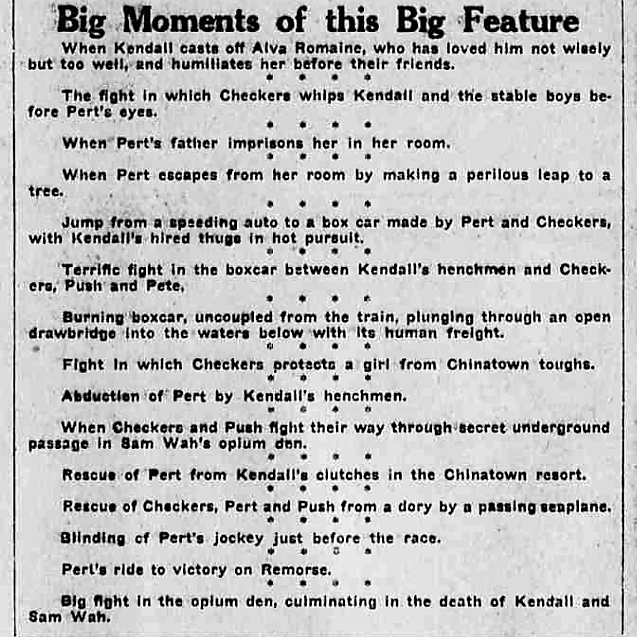

Jean Acker’s role in the screen version was that of the Heroine Pert Barlow. As Pert, Jean appeals to Checkers, Thomas’s character, a Racing Tout, to help her to stop her society Fiancee drinking so heavily. (The Fiancee, who’s played by Robert Elliot, is called Arthur Kendall.) When Checkers tries and fails, he and Pert find themselves in love, and become engaged; something her Father is so unhappy about, he locks her in her room. A daring escape follows. Then an elopement. With Acker’s Barlow taking with her her horse — named Remorse. The two decide to enter Remorse in a big local race. However, the evil Fiancee seeks to stop them, in any way he can, so his own horse can triumph. The pair overcome several serious obstacles – the wrecking of their train, Pert’s abduction and imprisonment in China Town and rescue, and the blinding of their chosen jockey – before succeeding in winning the competition. A feat achieved by Jean’s Barlow riding the steed to victory. After which, Bertram Marburgh’s Judge Barlow forgives them, and welcomes them back to the family home. The End.

If this re-phrased, contemporary synopsis doesn’t give the full picture, we can access an advertisement that perhaps fills in any blanks when it comes to action. (Above.) As we see Acker was back to her earlier self. Leaping from her room to a tree. Jumping from a “… speeding auto to a box car…” And riding “…. to victory on Remorse.” And once more, at the very end, anyway, cross-dressing and pretending to be a man. Not so common at the time. And in advance of the masquerading of both Dietrich and Garbo a decade later. (It’s only recently, too, that any female has been permitted to openly compete in a horse race.)

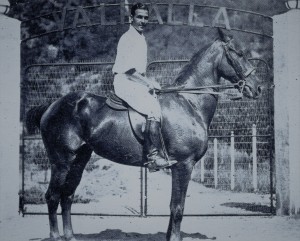

By mid. March filming had commenced on the East Coast, at the company’s studio, at Fort Lee. Sometime in the third or fourth week of the month, a writer at Motion Picture News put together a look at progress so far, including details of what footage had been shot of Jean up to that point. (The piece was published in the March 29th edition.) “… the little Broadway beauty and daredevil of the movies…” was offering to “bet one year’s salary” that when the horse featured (owned by P. S. P. Randolph) started in The Kentucky Derby, she’d be: “… in the saddle wearing the Randolph colors.” Acker, already “one of the best woman riders in the country”, had been, we’re informed, coached as to how to ride in an actual race by “a well-known retired jockey”. And had already been captured with the thoroughbred at the private track at: “… the Randolph Estate at Lakewood, N. J.” (If the June 21st edition of THE MOVING PICTURE WORLD is believed then the information that Jean Acker would indeed ride in The Kentucky Derby was just good old-fashioned Hoo-Ha. According to the publication: “The racing scenes were filmed at the Belmont Park, Long Island, and on a New Jersey course.”)

Many reports mention the fact that Stanton was “a stickler for realism”. The entire set erected for the gambling scene, was authentic, down to the ivory inlaid chips each worth $1.50. Chinatown was faithfully recreated, with the assistance of Captain Hannon, of the Elizabeth Street police station. And Acker’s ten foot spring from the roof of a mansion into the branches of a tree, 38 feet from the ground, was all too genuine. Just as genuine, was the injury sustained by Ellen Cassity, portraying third-billed Alva Romaine, hurt in the filming of the ballroom scene by a broken goblet. (The reporting of this doesn’t state exactly how the Actress was injured.)

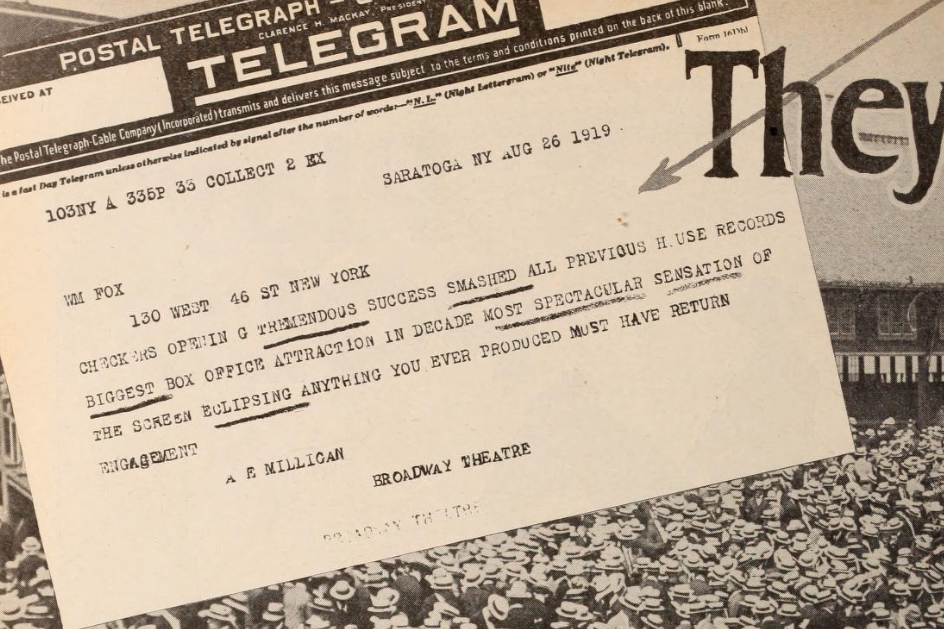

There’s no doubting that Checkers (1919) was a hit. A quick word search on lantern, or at Chronicling America, or Fulton History and elsewhere, provides plenty of proof. On July 28th, more than a month before the tightly edited, 70 minute visual extravaganza was issued, Wid’s DAILY was singing its praises. The Director: “… handled his material in such a way as to get every ounce of punch possible out of the story’s bigger moments.” It was edge of the seat stuff. Particularly the climax: “… when the picture showed the race itself, there was to be had almost as much excitement as if you had a big bet on the race yourself.” Others – THE NEW YORK CLIPPER (September 3rd), EXHIBITORS HERALD AND MOTOGRAPHY (September 6th), and PHOTOPLAY Magazine (October), as well as many more – all gave Checkers (1919) favourable reviews. Yet it was the feedback to industry publications from exhibitors that showed the extent to which the film succeeded. (There are, unfortunately, just too many examples to reproduce here, other than the one above.)

By the time Checkers (1919) premiered in St. Louis, the Author’s home town, with allsorts of publicity innovations – ten store windows devoted to publicity, a horse with a jockey parading in the streets, 500 paper strips with premiere details pasted to telephone poles, adverts accompanying 3,000 copies of the title tune, 5,000 windshield notifications, and even a preview advance Trailer playing in the “Wm. Fox Liberty Theatre” – employed, Jean Acker, “the little Broadway beauty and daredevil of the movies”, was firmly on the West Coast.

Why? And why was she no longer working for William Fox’s Fox Film Corp.? The only possible reason is that a jealous Nazimova had forbidden her to. And had forced Jean to relocate to California in order that she couldn’t soar higher. Acker’s wings needed to be clipped. And clipped they would be were she to be in the West. We know this, due to there being no customary announcement that Jean had left her current employer, or, unprecedented at the time, that she’d been signed by her new one. Madame, somehow strangely in control of the Miss, even managed to obliterate her recent achievements, when she was credited, by Cal York, in Plays and Players, in the September edition of PHOTOPLAY Magazine, as the person who’d discovered her.

Nazzy, recently returned from New York, had brought with her, in the following order: a collection of frogs and toads for her bathtub, a new brand of perfumed cigarettes, and Jeanne [sic] Acker, a Protege, who’d now be named Jeanne Mendoza. Jean’s humiliation was complete. Not only was she under the thumb of her older Lover, she’d failed to register, ahead of bathtoys and cigarettes, in one of Hollywood’s most prestigious publications. (And, most tragic of all, Lambert’s, Nazimova: A Biography, in reproducing this awful announcement, condemned her to a quarter of a century of derision.) Yet she at least at the time had a job (no doubt organized by Alla). As mentioned (at the very end of the sneering paragraph), she’d be playing opposite Bert Lytell, in a forthcoming Screen Classics Inc./Metro Pictures Corp. film, Lombardi, Ltd.

When I learned Jean Acker had been involved in the film version of Frederic and Fanny Hatton’s, three act, 1917 comedy, Lombardi, Ltd. (1919), I decided to seek it out. And I’m pleased I did – The British Library had a 1928 copy – as it gave me insight. Not only into what was going on in her life in terms of work, before she and Rudolph Valentino met in the Autumn of that year; but, the film being inaccessible to me, and no script copy being available, an excellent idea of what the adaptation was all about at its core. I suddenly had background. And suddenly a lot of what transpired made sense. (I later also accessed Dorothy Allison’s, scene-by-scene version, in the January 1920 issue of PHOTOPLAY.)

The play by the prolific Hattons, who’d previously scored hits with, Years of Discretion (1912), The Song Bird (1915), $2,000 A Night (1915) Upstairs and Down (1916)), and The Squab Farm (1916), was launched by Oliver Morosco, at his Morosco theatre, in Los Angeles, on July 1st, 1917; where it instantly succeeded, catapulting Leo Carrillo, who played the main character Tito Lombardi, to theatrical stardom. (NOTE: $2,000 A Night, was, interestingly, originally titled: The Great Lover.)

The story, in essence, is that of a brilliant, Italian male Modiste/Fashion Designer, who’s talented at creating desirable clothing, but not so clever when it comes to running the business and making a profit. Additionally, he’s unlucky in love; and continues to be so throughout the play, until he discovers true happiness under his nose, in the form of his faithful, but not-so-glamorous store Manageress. Many characters revolve around Tito. Two, an important Model named Daisy, the Ingenue Lead, and a secretly wealthy youth, named Riccardo, the Juvenile Lead, ultimately being most important to the narrative. A tale, summarized by Guy Price, in his review in THE LOS ANGELES EVENING HERALD, on Monday, July 2nd, 1917, as: “Real love [triumphing] over the selfish, for-gain-only, ‘surface love.'”

As it was Daisy that Jean portrayed in Lombardi, Ltd. (1919), I paid attention to her as a figure, and to her lines and interactions with Riccardo. In the DESCRIPTION OF CHARACTERS section, of the late ’20s reprint at The British Library, she’s described thus:

DAISY : A mannequin in Lombardi’s establishment.

Ingenue Lead. Of the ‘baby vampire’ type.

Played for comedy at all times. In the [F]irst [A]ct

innocent and unsophisticated. Commencing with

the Second Act she assumes the airs of the girls

about her, and thinks herself quite ‘wise.’ She

should be a young girl of about twenty-two,

rather small but possessed of a good figure and

very pretty. In Act 1 wears her hair low and

simply ; thereafter puts it on the top of her head

in exaggerated manner, but not so that it will

spoil her attractiveness. ‘Kittenish’ best des-

cribes her habitual manner.

And I also reproduce, Riccardo’s, or Rickey’s description, which I think very interesting, when you have in mind another, real-life Italian, that the actual day-to-day Jean would be encountering. As follows:

RICCARDO TOSSELLO : Juvenile and Light Comedy.

A young man of about twenty-five. Italian de-

scent. Not the swarthy type ; black or dark hair.

Does not use the Italian dialect any time. Is of

the manly type and easy to play if not ‘acted.’

Very wealthy, but does not seem to be aware of

the fact, and is never arrogant or important

because of his wealth. Just a ‘hail fellow well

met’ at all times, never loud in action, speech

or dress. The diamond rings he wears are sup-

posed to have been inherited from his father and

worn for the sake of their association, rather

than their value.

As you can see, I’ve purposely highlighted/made bold parts of sentences, for both Daisy and Riccardo/Rickey, that I feel, strongly, particularly with Riccardo Tossello, eerily echo his off-screen counterpart Rudolph Valentino. He’s named Riccardo/Rickey and Rudolph was Rudolph/Rudy. He’s 25 and Valentino, was, likewise, in his mid. twenties. (24 at this point.) He’s not swarthy, has black or dark hair, and doesn’t use the Italian dialect any time. And Rudy wasn’t swarthy, had dark hair, and didn’t, at least by 1919, as far as I know, use the Italian dialect. And further, Rudolph was never arrogant or important; was a hail fellow well met; and, as we know, rather enjoyed wearing rings. But back to Daisy/Jean and Rickey/Rudy in a little bit. As I now throw June Mathis into the mix. It being “The recognized head of Metro’s scenario department” who was responsible for the adaptation.

“Comedy is very necessary. But, after all, it doesn’t make the lasting impression that is made by the soul-searching story—the story that gets under the skins of all of us and reveals that mortals are weak, groping atoms in a cosmic wilderness and that into their brief span of existence is crowded infinitely more sorrow than happiness.”

June Mathis, quoted in Motion Picture News, August 9th, 1919.

The pre The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) Mathis had only recently been elevated to the enviable position of Metro Pictures Corp.’s Scenarist in Chief. And was being heralded as such, that Summer, in promotional pieces like the half page article, Woman to Adapt Screen Classics, that appeared in the August 9th edition of Motion Picture News. If the message wasn’t clear from the title, it was hammered home in the text, when it was stated that June was: “… grooming herself for a demonstration of her contention that the female of the species is more strenuous than the male…” in the scenario writing sphere. “Miss Mathis” had: “… established herself as a motion picture technician and one of the cleverest handlers of big situations, ranging from graceful comedy to heart-gripping drama.” The creation, by Metro Pictures Corp.’s production arm, Screen Classics, Inc., of ‘fewer, bigger and better’ productions, from September the 1st 1919, had her undivided attention. And she was quoted as saying: ‘Give me the human drama. Let it be a story about my fellow human beings—their hopes and fears, their joys and sorrows. Let me cry with them, but let them be human.’

Unaware of the forthcoming human drama of two fellow human beings, Acker and Valentino, almost under her very nose, individuals, with hopes, fears, joys and definite sorrows, Mathis adapted Lombardi, Ltd. according to her instincts. To get an idea of any differences between the stage version and the screen version we’ve only to look at reviews. Such as the complimentary one we see, in THE WASHINGTON HERALD, on Monday, October 20th, 1919. Which begins with the sentence: “Seldom in picturizing a former stage success has the original acting version been so strictly adhered to…” And went on to explain that: “The logical sequence of scenes has been scrupulously observed with the result that the shadow drama …. preserves all of the directness and all of the dramatic power of the play…” This information helps me to be certain that the cinematic Daisy wasn’t, despite being reduced slightly in importance by June, too dissimilar to the theatrical Daisy. Which is significant, given my belief the actions of both her character, and those of the opposite character, were a real influence on events.

In my post, December 1919, in December 2018, I looked in some detail at the run up to the meeting of Jean and Rudy — at least from his perspective. On a night in early September, Rudolph Valentino found himself at Venice nightspot, The Ship. Spotting friend Dagmar Godoswky, he approached her table, but met with rejection from Alla Nazimova — which triggered a rejection by all gathered. (Godowsky’s recollection was it was a celebration of the conclusion of shooting of Nazimova’s next spectacular.) Within days the humiliated Valentino became acquainted with a young woman present at the venue: Jean Acker. The location, this time, was the newly-bought home of the established stage and screen star Pauline Frederick. At this more congenial dinner party – Gavin Lambert’s claim that it marked the end of the filming of Madame X (1920) is incorrect as it began production the following Spring – Jean was alone.

Acker, I’m sure, instantly recognised the beautifully dressed, well-mannered Italian so horribly insulted by Madame Nazimova. After being introduced by ‘Polly’ he asked Jean to dance. She declined. Instead they sat under “a California moon” and talked, and talked — then, talked some more. The discussion is unrecorded. Yet we know that they found themselves understanding and liking one another. It was, after all, the collision of two rather similar people. Individuals who were somewhat battered and bruised by life and their profession. Victims, both, of the great Diva Nazzy. The Force. Someone that, as Dagmar Godowsky explains, in First Person Plural: The Lives of DAGMAR GODOWSKY, by Herself (1958), her autobiography, only: “… had to raise an eyebrow and everyone shook.” (Rudy was to call Dagmar a couple of days afterwards to tell her all about it and how he felt about Jean.)

Miss Acker probably spoke of her return to the profession the previous year, her arrival on the West Coast, and her most recent film. It would be strange – impossible – for her not to have told him all about Metro Pictures Corp. and the powerful people she knew there. And of her plans for the future. Mr. Valentino had his own tale to tell of course. How he’d got started in the business in 1916; had shifted West the following year; about his serious struggles; and how he’d recently completed working with Clara Kimball Young, in Eyes of Youth (1919). Likewise, it would be odd, odd and unlikely, for him not to ask questions about Metro Pictures Corp. About June Mathis. And about Maxwell Karger. And to see if they had mutual friends. (After all they’d both spent many years in New York and its environs.) If Jean, so recently Daisy, didn’t yet see in Rudy a Rickey, she certainly saw a young man that she felt she could trust. Someone she could enjoy being with and maybe see again. If not, then why did they see one another again? And then again? Was he, I wonder, employing his “credo”, as reproduced in a newspaper, in 1922? 1. Never play at love unless you feel the urge. Insincere lovemaking is cheating—and you cheat yourself most of all. 2. Never try cave-man tactics on the woman you love. That’s a sure way to lose her if she’s worth winning. 3. Be patient. Never try to kiss a woman the first or the second time you meet her. And never reveal your purpose, whatever it may be, until she is used to you and trusts you. Perhaps, like me, you picture her receiving a tender kiss on the hand as they said farewell — not a difficult thing to imagine!

Over the next eight weeks they saw one another irregularly. Though Lombardi, Ltd. (1919) had been wrapped (at least for Jean and the principals), by the time of the Frederick soiree, it appears Acker was busy for some of the time working on The Blue Bandana (1919); a Robertson-Cole Productions film, the Star of which was William Desmond. (Having been considered “specially fitted for the part” of Ruth Yancy, she’d been loaned out, and the movie was released, quickly, on November 16th.) On his side, Rudolph’s latest role, as Cabaret Parasite, Clarence Morgan, in Eyes of Youth (1919), was very much In The Can. And he was at a loose end, not having yet secured the part of Prince Angelo Della Robbia, in Passion’s Playground (1920). Contractless, and without a studio, he would, between their dates, be looking for his next opportunity. (I begin to think it was at this time that he went to see Sessue Hayakawa, to ask about joining his company, at the facility at which Jean was at work. Something mentioned in Sessue’s autobiography, ZEN showed me the Way… to peace, happiness and tranquility and harmony (1960), on page 144. He also says Acker worked for him after they’d married.)

No doubt they went on a short trip or two in Jean Acker’s auto. And enjoyed an evening here or there dancing. Being outdoor types, and accomplished riders, they absolutely rode in the Hollywood Hills — in fact, we know they did. And it would be surprising if they hadn’t seen at least one motion picture. Is it possible that they went to watch the September 16th evening preview of Lombardi, Ltd. (1919), at the Hollywood Theatre, at 6724 Hollywood Boulevard? I think so. And it’s quite likely, in the following month, the couple could’ve enjoyed an advance screening of Eyes of Youth (1919), as such private viewings were happening in October, in advance of a big trade preview in New York, on the 30th. Fun for them both, if so. Despite it emphasizing the real differences in their positions in the industry. Jean was, so far, more experienced and more successful; was better known and better connected; and, receiving a regular weekly salary of several hundred dollars.

A couple of years later, in Chapter Three of My Life Story, his life so far, as related to PHOTOPLAY Magazine, and published in their April 1923 edition, Valentino went into some detail. Firstly: “It was at a party at Miss Frederick’s that I met Miss Jean Acker. I thought her very attractive. But I did not see her again for some time.” After meeting her once more: “I fell in love with her. I think you might call it love at first sight.” Reminiscing about their horseride: “It was like an Italian day. Romance was shining everywhere, and the world looked beautiful. That day I proposed to Miss Acker. It seemed spontaneous and beautiful then. But as I look back, now, it seems more like a scene [from] a picture with me acting the leading part.”

I feel, here, it’s worth looking at the conversations about matrimony between Daisy and Rickey, in Lombardi, Ltd. Though the dialogue would’ve been seriously pruned for intertitling, I’m certain the general tone was retained. Pages 106, 107 and 108, in Act II, as follows:

Page 106

RICKEY. (At R. of DAISY and close to her) Say, ducks, I must have you. Just naturally must. And you might just as well slip me that “Yes” now, because I’ll bother you to death till you do. Come on, will you have me, lovey ?

DAISY. Are you offering me marriage ?

RICKEY. Surest thing you know. Honourable marriage. (Takes both hands in his and leads her so that she is just R. of lower end of the settee.) Bride’s cake, veils, rice and that little gold band that your sex thinks so well of, and besides that, Daisy, l-o-v-e, and I’m full of it.

DAISY. (Backing to corner of settee for support) It’s my first ! (Sits on settee.) My ! It does give you a thrilling feeling, just like the books say. Have you asked many other girls that ?

RICKEY. What ? To marry me ? (Sits next to Daisy on settee above her.)

DAISY. Uh, huh !

RICKEY. Peaches, you are number one absolutely. Daisy, you’re the first little woman I ever saw that I wanted to make the Mrs.

DAISY. Yes, I bet I am !

RICKEY. (Laughing.) You are.

DAISY. Oh, yes. Oh, yes. Doubtless. Doubtless.

RICKEY. I’ve had some flirts, of course. I don’t set up to be a Saint Anthony, but wedding rings; no, lovey lamb, just my little Daisy. (Embraces her.)

Page 107

DAISY. (Gives audible sign of content.) Oh, I just wish you wasn’t a chauffeur, because I do like you—lots. (Breaking away from his embrace.) Only, I can’t—honest, I can’t. (Rising and crossing to c.)

RICKEY. (Rises and shows disappointment) Why, Daisy ?

DAISY. I’ve made up my mind I’m going to have things and money and lots of it.

RICKEY. (Following DAISY) But I love you, Daisy, and I’ll make you love me. Won’t you take a chance ?

DAISY. (Waving him off) Now, please go away. I don’t want to say, “Yes.” I’m not going to marry a mechanic. (Crossing to R. below table.) I cannot do it. (Continues around R. of table and above it.)

RICKEY. (Disappointed, but still persisting, he crosses up L. of table and meets DAISY just above it) Well, all right, if that’s the way you feel about it, but, Daisy, I want you to know that I would carry you around on my two hands. (Extends his hands palms up, forgetting that he had previously turned the rings he is wearing.)

DAISY. (About to take his hands, notices the diamonds in his rings; staggers) My Gawd ! Are those stones gen-u-ine ?

RICKEY. Eh? Oh, yes. Belonged to my father. Want one? (Taking off ring from left hand.)

DAISY. Oh, you mean it ? (RICKEY puts ring on her finger.) Ain’t it swell. I never did see one bigger. But it wouldn’t be right because I ain’t goin’ to swerve from my purpose—take it off, please.

(Pause. DAISY takes off the ring, handing it to RICKEY, who replaces it on his finger as she continues speech.)

RICKEY. It’s yours; it’s for you.

DAISY. I just wish I could see my way clear to…

Page 108

taking it, and you, too, Mr.—what’s that queer name you’ve got ?

RICKEY. Never mind, Daisy. Just call me Rickey. My name is Italian and your dear little lips could never pronounce it.

DAISY. (In astonishment) Are you Eye-Talian ? Oh, that’s grand.

RICKEY. Wouldn’t you like to try some Italian hugs today ?

DAISY. Oh, maybe—I might.

I find this exchange between Daisy and Rickey in the play quite startling. Of course this isn’t Jean and Rudy, yet, the similarites between the stage characters that became screen characters, and the actual people, who were screen performers and became a couple, albeit briefly, is remarkable. And the sequence I retype couldn’t be more aligned. Even though, as I say, it would’ve been seriously boiled down, in terms of explanatory text insertions between frames, in the Metro Pictures Corp. adaptation.

Daisy’s very uncertain. (As Jean obviously was.) Rickey subjects her to repeated requests and is persistent. (As Rudy reportedly did and was.) The pursued is clear his (apparent) lowly position is a serious obstacle. (Valentino wasn’t as notable as Acker.) Daisy remains resolved and won’t be swerved. (Jean was likewise resolute.) Rickey’s surname’s difficult to pronounce. (As was Rudy’s which was Guglielmi.) We can only wonder if the back and forth between Daisy and Rickey after the reproduced segment was similar in reality. And if, like her onstage self, the offstage Acker suggested that they should: … be pals and play around and not talk about getting married so soon? Yet, get married Acker and Valentino did after all, and soon. Around midnight, on Wednesday, the 5th of November, 1919.

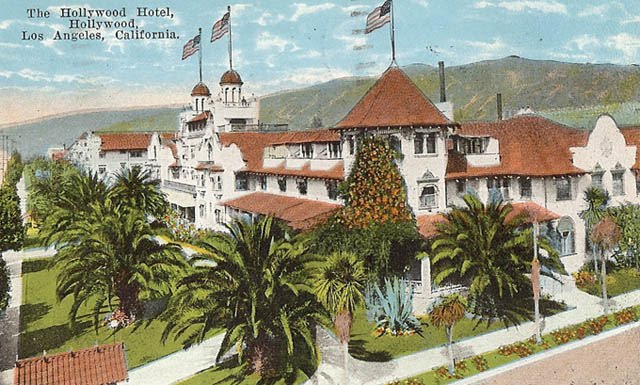

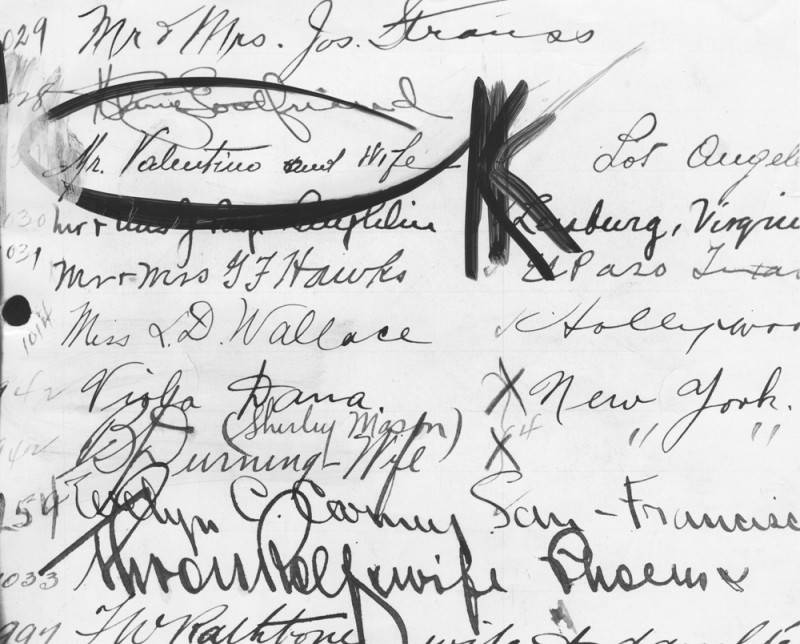

There are, remarkably, two versions of what happened, and how it all came to pass. And while not dramatically different, they’re diferent enough to have us wondering which is correct. In the first, the pair had been riding on the 5th, probably in the morning, and Jean received her seventh proposal and was invited to elope to Santa Ana that day, but declined both the suggestion of marriage and the elopement. Mostly, this was due to the fact the pair, or one of them, had been invited to an important event that night; a party being thrown for Mr. and Mrs. Richard A. Rowland, President of Metro Pictures Corp., by Joseph W. Engel, the company Treasurer, at his home. It was at this gathering that the two sweethearts were encouraged by friends to wed. Resulting in a mad rush to secure a licence and a Minister/Priest by the end of the day. (The Officiator was the Rev. James I Myers of the Broadway Christian Church.) The second version begins in the same way, with a ride, except, on the previous day, the 4th. In this alternative account, Acker accepted the final matrimonial invitation, and later that day Valentino ran into Maxwell Karger (at an unknown Hollywood hotel (which was likely The Hollywood Hotel)). Mr. Karger, Jean’s Boss at her studio, having learned from Rudy about their plans, suggested they marry at the celebration for the Rowlands, the next evening, at the home of Engel. All leading to a great deal of driving around in Jean Acker’s car, on that day and the next, to arrange everything. And nuptials at the party by midnight on the 5th. The spectators, besides Mr. and Mrs. Engel, Mr. and Mrs. Rowland, and Mr. and Mrs. Karger, included Mr. and Mrs. Fred Warren, May Allison, Herbert Blache, [J.] Frank Brockliss and Charles Brown. (The latter version, corroborated by PHOTOPLAY Magazine, is from Natacha Rambova’s serialized 1930 look at her late former Husband’s life and career, The Truth About Rudolph Valentino.)

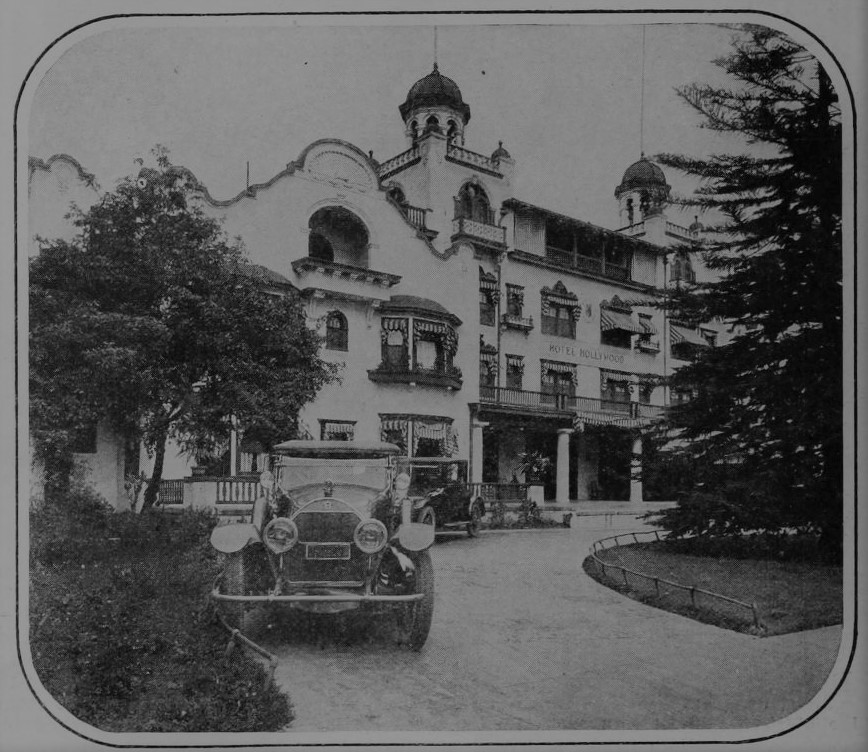

Whichever’s truest, after their respective I dos, champagne and many congratulations, they headed by themselves for the famous Hotel Hollywood (a place which had once sheltered Alla Nazimova), where Jean was then accommodated. On leaving the location of the ceremony they were unquestionably on a high. Happy. Smiling. And looking ahead with optimism to married life. Waved off by the Engels, the Rowlands, the Kargers and the others, and with perhaps a couple of tin cans tied to Acker’s auto., they drove off into matrimony, with every reason to expect that it was to be blissful. So, awful it was, when, in between the door of the Engel’s abode and the door to Acker’s hotel room, something unpleasant happened.

Several decades later, a young Patricia Neal, who’d befriended Jean Acker, and was renting an apartment from her (in a block she owned in Beverly Hills), was at some point informed by her Landlady that, soon after the exchanging of vows, Rudolph Valentino had told his Bride he’d once suffered from a sexually-transmitted disease: Gonhorrea. In her early 2000s biography, Dark Lover: The Life and Death of Rudolph Valentino (2003), Emily W. Leider reveals (in the NOTES section), this was information supplied to her in a personal communication with the Actress in 1998. And, in MISALLIANCE, the chapter in question, advises the reader that it’s credible, due to it being: “confided in private to a friend…” At the time of writing, and before and after publication, Leider didn’t have at her disposal information later made available by Jeanine Therese Villalobos, in her dissertation, Rudolph Valentino: The Early Years, 1895-1920. That dissertation presents evidence that the fourteen-year-old Rodolfo actually contracted Syphilis, in a brothel, in Taranto. And that he spent a long time in bed recovering; and it was during this lengthy spell in his room, that he mentioned it to a friend in a letter.

While he was, Jeanine proposes, potentially symptom free in 1919, he felt duty bound to admit his former affliction. Whenever it happened – in the vehicle when they arrived, or, on a comfortable banquette inside of Hotel Hollywood – it was obviously a terrible blow for his Bride. This female, who’d been so cautious with males, and had had, I’m certain, previous unpleasant experiences, and who’d found herself trusting Rodolfo Guglielmi to the point of becoming his Wife, must’ve been very shocked. It appears that she somehow slipped away, got the key to her room, and went inside and locked the door.

Following her a little later, and attempting to enter and finding he was unable to, the Bridegroom became angry and knocked loudly, and then began hammering. Inside, his Wife, tearfully told him to go away and leave her alone. Which he subsequently did, the noise having awoken guests, who probably remonstrated. He was it seems confused by her behaviour. Perplexed. At a loss. His retreat to his own rooms must’ve been a sad and sorry one. And it’s doubtful he slept unless out of sheer exhaustion. Not long afterwards Jean left her room and went to see Mrs. Anna Karger. Once in her presence she declared that getting married had been a terrible mistake. Sufficiently soothed, Acker then left the Kargers, and headed to her girlfriend Grace Darmond’s home.

Almost immediately newspapers and trade publications reported the hasty union. One of the earliest, was Wid’s DAILY, on Saturday, November 8th, 1919. As follows:

Married at Midnight

Hollywood—Jean Acker who

played Daisy the model in Metro’s

“Lombardi, Ltd.,” married Rodolpho

Valentino, an actor, at midnight

Wednesday.

In Lombardi Miss Acker was in

love with a young Italian whom she

then marries.

Joseph Engel of Metro, had an af-

fair at his home at which Jean and

Valentino were present when they

decided to get married.

At midnight, then, they they searched

for a license clerk and a minister.

He and Mrs. Karger were

witnesses to the ceremony.

Incredibly the story kept being printed for about two months, long after it had all gone sour, and Rudy had nearly spent Christmas 1919 alone. After telling him, a day or two later, that they’d made a mistake and could never be happy, Jean successfully evaded Rudy for the rest of November; during which time he repeatedly telephoned, attempted, unsuccessfully, to see her (at Hotel Hollywood and at Darmond’s), and wrote to her. A letter from him that month on the 22nd ended: “Understand that you will make the trip to New York absolutely against my will and that I’m always ready to furnish you with a home and all the comforts to the best of my moderate means and ability, as well as all the love and care of a husband for his dear little wife. Please, Jean, darling, come to your senses and give me an opportunity to prove to you my sincere love and eternal devotion. Rudolph.”

It would seem that Valentino’s constant attempts to get through to Acker eventually paid off. According to the testimony of steadfast friend, Dougie Gerrard, at their divorce trial in December 1921, Jean Acker was brought to his flat/apartment by Rudolph Valentino sometime soon after the communication of the 22nd. (A week later, or, possibly longer.) “I suggested going to the Alexandria. This was agreeable.” he stated. “I said to myself: ‘That’s alright; they are together, thank God.’ ” Yet, the reunion was a temporary one, as he revealed. The next day Rudy was ecstatic. But the day after he appeared at Gerrard’s to tell him that Mrs. Guglielmi had once again left him. Amazed, Dougie took matters into his own hands, and telephoned Jean to see what the problem was. “I asked her why she and her husband could not live together. She said: ‘He is impossible, he is dictatorial and I’m not going to live with him any more.’ ”

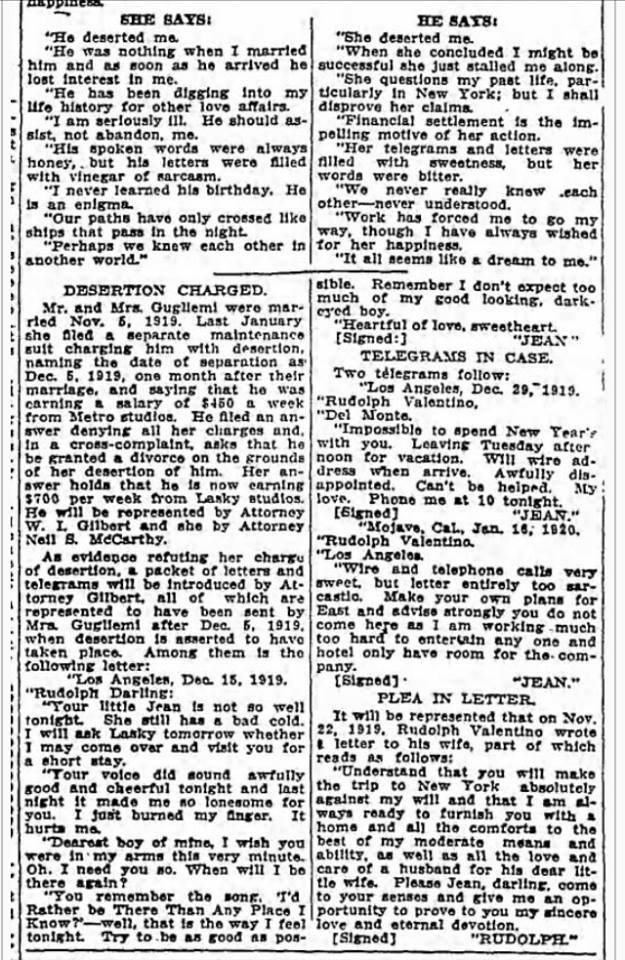

Looking at her communications afterwards makes it difficult to take her side. In a letter, dated December 15th, clearly composed after a ‘phone conversation, she wrote: “Rudolph Darling… Your voice did sound awfully good and cheerful tonight and last night it made me so lonesome for you. …. Dearest boy of mine I wish you were in my arms… When will I be there again? …. Heartful of love, sweetheart. JEAN.” And in a Telegram on December 29th: “Impossible to spend New Year’s with you. Leaving Tuesday afternoon for vacation. Will wire address when arrive. Awfully disappointed. Can’t be helped. My love. Phone me at 10 tonight. JEAN.

What could account for Jean Acker being so physically distant yet so emotionally close? Putting aside his revelation, which he may again have mentioned and reassured her about, there’s a clue in his letter in late November, and her response to Dougie Gerrard’s question. Rudolph Valentino was telling her what she could and couldn’t do. Her trip to New York wasn’t acceptable to him. And being told this wasn’t acceptable to her. I think the phrase he employs, “dear little wife”, says a great deal about his general attitude. An attitude that the “dear little wife” highlighted in another Telegram from January 16th. “Wire and telephone calls very sweet, but letter entirely too sarcastic. Make your own plans for the East and advise strongly you do not come here as I am working much too hard to entertain anyone and hotel only have room for the company.” JEAN. The Bride was obviously bridling.

Acker was, of course, a person on the whole very used to making up her own mind. It’s plain to me, and hopefully to you, that since her start eight years earlier, at the end of 1911, she’d managed to find a way to be independent of a man, if not of men, in a male-dominated era. And to be expected to become dependent, be subservient, be his Little Wife, was next to impossible. Unthinkable, even.

I strongly feel Jean Acker saw in Rudolph Valentino, if only fleetingly, and up to their nuptials, a person that she could unite with. A kindred spirit. I think that he engaged her in such a way and on such a level that he broke down her defences. I think, too, she saw, as I’m sure he did in her, somebody that could help her be more accepted. Someone that might make her look like everyone else in Hollywood. A place where many were united in marriage and enjoyed the resulting camaraderie.

Yet, it wasn’t, on both sides, to be. Jean didn’t receive a visit in Mojave in January from Rudolph. And he did make his own plans for the East. (A trip which would prove to be fateful.) However, despite their inability to make a go of it, they were, as we know, to remain married for another two years. And not only that, as will be seen in Part Three, connected, entwined, interwoven, call-it-what-you-will, not just until the dissolution of their marriage, but beyond. Even beyond the death of Rudolph Valentino. And, as this post demonstrates, beyond the death of Jean Acker. And even beyond this post. Chained for all eternity, down through time, forever.

Thank you for reading this post in its entirety — I appreciate it. As usual, any and all references and research is available to anybody who asks, if they’re not already provided in the text, as a link, or, as an image. I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about Jean Acker’s life and career as much as I enjoyed writing about it. The third instalment, looking, in quick succession, at the divorce, her adoption of the name Jean Acker Valentino, her film career in the Twenties, the demise of her Husband, her ups and downs afterwards, her comeback, and the years of non-stardom, will be posted a month from now, in February. See you then!

Grazie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure.

LikeLike

Simon, this is a major ‘AWAREhouse’ of information! So much detail about the unfortunate wedding and ‘honeymoon.’ The ‘he said, she said’ afterward which I had never read before! I enjoyed the brief but very interesting look into June Mathis. (Speaking of which, I’m sure hoping that blogs about her are in the future!) And, most of all, the detailed, intimate look into Jean—her work, everything. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And thank you, too. It’s a problematic one. People take sides and I understand that. I’m not, believe-it-or-not, a side taker. I get forced to, from time to time, in unjust situations, but I usually like to be fair to both parties. Or not get involved. Rudy wasn’t perfect and he knew it and that’s a big part of his personality but obv. it’s another topic. I do wish the in-the-works Mathis bio. was out already. If it isn’t in the coming 12 months I may celebrate her (if I can squeeze it in). I mean, someone has to, right? Look out for Part Three next month!

LikeLike

Fascinating account of Jean Acker, of whom I knew very little.

I appreciate how fair you try to be to both sides. That’s part of what makes your essays so interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. Had her papers been gifted to an archive, or museum, I would’ve written her bio. as planned, and had it out already. What little there is so scattered. And there are few people alive now that knew her well. If she never has one, at least this will be out there, with a possible, additional, future post or two if I run across anything else. I have to say that Part Three isn’t going to conceal any of her activities that were questionable. But in the context of the times they do make more sense — IF we look at the context of the times which people don’t. And you know something? When you read, that in 1922, during his Bigamy trial, they chatted and were friendly, it does make you wonder if it wasn’t all Hoo Ha at the end of the day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, people don’t often look at things in the context of their time, as you say.

As an aside, today I watched The Stork Club (1945) and was surprised to discover Jean Acker has an uncredited role as a clothing sales lady…if it’s the same Jean Acker?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooh! Yes! It’s her! Do you see her?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Simon, Just finished reading, and although i do know a lot of the info written, there was so much that I never heard at any other time. You sure did your research and I enjoyed it very much. So much to think about, and a lot of unanswered questions that to this day still has me wondering and wanting to know. Thank-You, Very enlightening!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Karen! And thanks for stopping by! AND for commenting! Yes, this is why his pre fame years fascinate me so much, because there’s much left to uncover, and, revisit. Compared with his post fame period, which is almost accounted for every week or so, if not every day, exactly, his earlier times aren’t. Months of his existence are sketchy. For example, in most biographies, there’s NO info. about September 1916 to March 1917. (If I recall correctly Noel Botham’s bio. skips an entire year!) I feel it’s my job to bring forth any nuggets I can find to make him more whole than he’s been to date. Many of his life-long friends were connected with between 1913 and 1921. And much happened that impacted him later. Jean being one of the most significant people — along with June and Natacha. Part Three and Part Four are coming. I do hope to have your opinion about them when they’re posted. Please Stay Safe in the meantime!

LikeLike