Wonderful it is, to be invited to contribute to the April 3rd to 5th, 2020 Classic Literature On Film Blogathon, hosted by Paul, from Silver Screen Classics. As His Fame Still Lives is focused monthly on Rudolph Valentino, it’ll come as no surprise that it’s one of his films that’s the subject. Which one? Well, read on and see!

It’s amazing, considering his on-screen persona, that Rudolph Valentino appeared in only two motion pictures that were adaptations of great classic works. After all, this was a Twenties Super Star that veritably dripped with: emotion, romance, tragedy and history. All of his post fame vehicles – there were fourteen in total – are seemingly crammed, at least in our minds, with everything that makes a written work eternally appealing; which, according to Esther Lombardi, is: “… love, hate, death, life, and faith…” In visual terms, we think of him classically — in fact, he was promoted thus. Astride a horse. On a throne. Brandishing a rapier. Masked. With Terry, Ayres, Swanson, Lee, Naldi, Daniels, D’Algy and Banky in his arms. Ageless, spine-tingling, resonant, reverberating imagery.

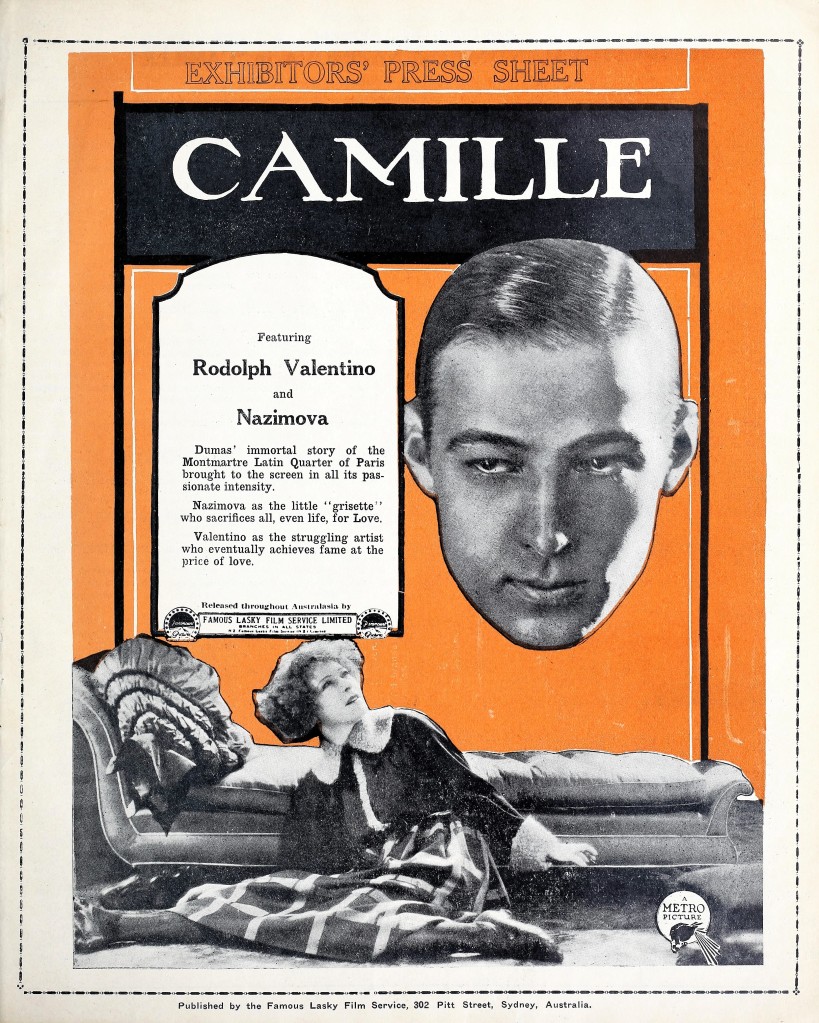

And yet, as I stated, just a pair. And from the same company and unleashed in the same year. Of these two productions, The Conquering Power (1921), based on Eugenie Grandet (1833) by Honore de Balzac, and Camille (1921), based on La Dame aux Camelias (1848) by Alexandre Dumas fils (both, incidentally, modern interpretations), I choose the latter. Not only is it, in my opinion, the better tale, it’s also the superior movie. And, as it has at it’s heart, as the Star and Anti-Heroine, the distinct, larger-than-life Silent Era personality, Alla Nazimova, it guarantees to be something of an information confetti bomb. (NOTE: while it’s true that the basis for, The Eagle (1925), Alexander Pushkin’s Dubrovsky (1841), is of the classic period, I don’t include it, due to it not only being an unfinished work, but also, because Pushkin wasn’t a novelist of the stature of either Balzac and Dumas fils. Also, it hasn’t reached the same heights, in terms of adaptation; as a ballet, an opera, or a play, for example.)

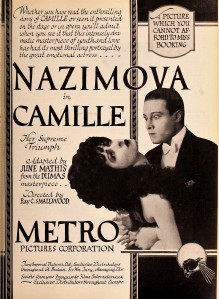

It was on Page Six of their Saturday, December 18th, 1920 edition, that Camera! THE DIGEST OF THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY revealed, in a brief sentence, that Alla Nazimova’s next vehicle for Metro Pictures Corp. was to be Camille. Her planned super-production, Aphrodite, based on the 1896 Pierre Louys novel, had been put to the side, and was expected to follow. According to the Star’s Biographer, Gavin Lambert, this change was due to the Director-General, Max Karger, being: “… shocked to discover just how perversely erotic and violent a movie…” had been outlined. Far more likely in my opinion is that it was shelved simply because Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount had secured “world rights” twelve months previously. Besides, a tale based on the brief life of a consumptive Prostitute, who’d died in Paris, in 1847, wasn’t exactly Sunday School territory. (Lynn Gardner’s excellent 2003 look at Dumas fils’ inspiration can be enjoyed here.)

Regardless of the reasons that La Dame aux Camelias was settled on – most likely at the suggestion of June Mathis – there’s little doubt the great Diva Nazzy sought to revive her flagging film career. To this end, it was seemingly decided, early in production, that the adaptation would break with previous picturizations (of which there had already been many), by being set in the then present day. And, that it would also, as Michael Morris points out in his biography of Natacha Rambova, Madam Valentino: The Many Lives of Natacha Rambova (1991), “… reflect the latest developments in European architectural and fashion design.” Something which wouldn’t only assist with promoting the motion picture, but also: “… foster in American film audiences a greater appreciation for art itself.” Nazimova’s other means of refreshing herself, was to secure a Leading Man of note, namely: Rudolph Valentino.

Valentino, who’d already completed work on the The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), the yet-to-be released Metro Pictures Corp. film that would make him a Star, was busy filming Uncharted Seas (1921), when he was brought to the attention of his future Wife. A moment she described in detail, exactly a decade later, in her serialized look at his life and career, and their life together: The Truth About Rudolph Valentino. ‘Mlle. Rambova’, who’d been been tasked, by Nazimova, with the design of both the costumes and the sets of Camille, hadn’t failed to notice her future Husband around the studio. Known to all as ‘The Wop’, he was an: “… aggressive, affable young man …. who, with his friend Paul, a young Serbian cameraman, was always under foot, determined to be seen.” (Natacha later heard from him that he’d bet Paul (Ivano) she would notice him one day. And that her chilliness and remoteness was a challenge.) Further:

“The introduction finally came while Mme. Nazimova, whose [Art Director] I was, was searching for a leading man. For weeks she had been combing Hollywood for the proper Armand for her “Camille.” Dozens of aspirants had applied, but something was wrong with each of them, until we had well nigh despaired of a hero. Then June Mathis, who had written the script of “Four Horsemen,” told us of the young Italian who had played Julio in that picture and whom she considered a genuine find. She suggested we give him a trial. Without much hope, we agreed to look him over.

One day, in Hollywood, the door of my office opened to admit Nazimova, followed by a bulky figure dressed in fur from head to foot. I had a glimpse of dark, slanting eyes between brows and lashes white with mica, the artificial snow of the camera world. Down his face perspiration was streaming in rivers, to complete the ruin of his makeup. The effect was not impressive. Here, I thought, is the very worst yet.”

Rambova goes on the explain how the “polar bear” shook her hand (a little too firmly), “apologized for his appearance”, and revealed that he’d been standing in the sun for two long hours “making close-ups of an Arctic scene”. Before dashing back, he asked her to: ‘Please say a good word for me to madame.’ Despite having noticed his “dazzling smile”, and having received, before his departure, a click of the heels and a polite bow, Natacha continued to be sceptical; that is, until they were forced together to see if anything could be done about his “patent-leather” hair. As she revealed later in the relevant installment: “The Armand of our script was an unsophisticated French boy from the provinces, who certainly had never seen hair pomade.” After much protestation, Rudy was persuaded to shampoo his locks, and then further persuaded to have his hair curled. “When finished the effect was not so bad.” Natacha explains. Adding: “Madame was delighted and even Rudy grew amenable when he saw the result of the screen tests. There was nothing he loved like characterization; to be all dressed up for a part fired his romantic imagination. It was agreed he should be our new leading man.”

Rudolph Valentino certainly had before him a great opportunity to become a character and to be dressed up. Likewise, there’s no doubt that, despite her waning popularity, the chance to work with the legendary Nazimova was indeed a once-in-a-life-time one. One which would enable him to improve himself, as well as to rise up a level in the business. Did Alla – Peter or Mimi to her friends – communicate to him what she communicated to Gladys Hall and Adele Whitely Fletcher in late 1921? That she’d planned never to portray the Lady of the Camellias until she had: “… forgotten how she had seen ‘Camille’ played.”? It’s hard to say. Certainly, she knew in him, as we see when we view it, that she’d found the sort of Armand Duval that her persona, Marguerite Gautier, could love. Yet, if she thought that she could overshadow the rising Star, and make him secondary to her, she was very much mistaken.

Camille (1921) commences with beautiful opening titles that immediately set the tone. The Camellia bordered text, after informing us METRO PRESENTS Nazimova, tells us, upfont, that it’s a modernized version. And then, after revealing that it’s Directed by Ray Smallwood, give us, one-by-one, the names of the triumvirate of women in reality responsible for the film. The Writer, June Mathis; the Art Director, Natasha Rambova; and the Star Producer, Nazimova. Interestingly, the tight cast of nine is headed by Valentino, as his name appears first in the list, followed by the other principals. Portrayed by: Rex Cherryman, Arthur Hoyt, Zeffie Tilbury, Patsy Ruth Miller, Elinor Oliver, William Orlamond and Consuelo Flowerton. With Alla’s main character, strangely, at the very end. If this was purposefully done, due to Rudolph’s fame by the time of release, or, was because he’s the first of the two main players to appear, is hard to say. Either way, it’s symbolic of her coming tumble from the top. (It could be that the version accessed was the later re-issue.)

After explanatory and scene-setting titles, the camera iris opens on an astonishing and eye-catching, fluid, marbled theatre staircase, apparently partly inspired by the style of Hans Poelzig’s recently completed, The Great Playhouse, in Berlin. At least two hundred extras descend the staggering construction. And soon we’re zooming in on Armand Duval and his good friend, Gaston Rieux; played, respectively, by Rudolph Valentino and Rex Cherryman. The pair chit-chat part of the way down as their fellow theatregoers pass them by.

We next see La Dame aux Camellias, Alla Nazimova, as she passes through an archway at the top of the steps, and pauses by the marbled parapet surrounded by men. An intertitle tells us: She was a useless ornament—a plaything—a bird of passage—a momentary aurora. This is an important moment already, as, when Camille is spotted by Gaston, and then by Armand, his friend, we see the instant fascination of the naive provincial with the decorative, and plainly worldly Marguerite. We also see Nazimova’s main character dressed in a striking, sheer, Aubrey Beardsleyesque, long-sleeved coat, covered in flowers, with a dramatic and over-long train, that appears to be edged with fur at its end.

When introduced on the staircase Marguerite is playfully dismissive of the – to her eyes and to ours – guileless new comer. As is her nature, she toys with him. And, after hearing that he’s a Law Student utters her first discernible line: “A law student? He’d do better to study love!” Armand is visibly pained, and yet remains so irresistably drawn to her, that, when the next character introduced reveals that the departing Camille will be hosting a supper party, he requests they go, which they do.

In a review, in the December edition of Motion Picture Magazine, Adele Whitely Fletcher declared, that she believed the settings: “… detracted from the characters and the action.” And it can be said, that the next scene, the party, is probably the best example of this competition between the decor and the players. The iris expands, this time, on the entry vestibule of Marguerite’s up-to-the-minute abode. And through a shimmery, see-through curtain, we see the Hostess and her animated guests arriving. After the curtain is parted, and they all pass through, we’re in the reception room; a space which forces the eye to move from the piano, to a pouf, to a rug, to an arch, to a day-bed, then back again, as the invitees enter before depositing themselves. (Rambova’s creativity hasn’t, however, yet run riot!)

Alla’s Marguerite escapes her pursuer (Hoyt’s Count), after being framed, nicely, in the largest arch of all, the dramatic, glass-doored entrance to her boudoir. Once inside, she manages to have a brief rest – her Servant, Nanine, tells her she’s ill and needs to call a Doctor – before the arrival of Rudy’s Armand, Rex’s Gaston and Tilbury’s Prudence. She initially looks exhausted, as she surely is, however, her look into the mirror, suggests an individual trapped, and unable to escape the whirl and tired of it. Yet emerge she must, and she does so, ready to entertain those gathered — something she’s clearly done many times before. Here, I love how she casually flicks the switch that instantly brings to life all of the decorative lights that edge the third archway; which is how a seated area, immediately to be put to use, is accessed. For me, the switched-on lights echo the way in which she switches on her own inner illumination, before exiting her bedroom.

The glassed-in alcove, with its food and drink laden tables, is where action is focused for the next few minutes. Armand, Gaston and Prudence arrive in a subdued manner, which contrasts nicely with the earlier, much more numerous arrivals. The party’s in full swing already as Marguerite rises to greet the trio. Then, learning that the muted and nervous Duval is crazy about her, she’s once more flippant. Saying to him, as she’d said already to her Lover, the Comte de Varville: “Not until you put a jewel in my hand.”

The supper party continues. Camille is frivolously solicitous of Armand, much to the distaste of the Count, who throws down his napkin angrily. Gaston, meanwhile, behaves like an expectant pet with Prudence, who denies him a forkfull of food at the last minute. To placate the unhappy Count, Marguerite Gautier rises from the seat she shares with the smitten youth, stands tall and breaks into a tributary, but unsatisfactory rhyme. Both the wording and her subsequent behaviour fail to alter the mood of her Sponsor. And, as she drains dry her glass, we see the fuming Count and the puzzled, confused Student Lawyer to her right. Two pathways: the current and the future.

An autobiographical song from the Hostess follows, which is interrupted by the arrival of Pasty Ruth Miller’s, Nichette; who, we discover, thanks to an intertitle: “… used to work in the dressmaking shop with Marguerite.” Alla and Patsy Ruth’s series of kisses on the lips are noteworthy here. As is her defending of her, against the really rather pathetic/sweet onslaught of Rex, as Gaston. Who, despite his drunken state, realises he needs to be more considerate and polite. (A look, here, between Cherryman and Miller, is all we need to see to know that something will develop between them.)

Next, both the intoxicated Gaston and the infatuated Armand are prevented, by Camille, from departing. The Hostess dances with Armand’s friend (much to the annoyance of the Count). The others occupy themselves. Then, the opening of a window, for air, induces a serious coughing fit, and Marguerite’s forced to retreat to her bedroom. Armand sees that she’s unwell and watches powerless. He approaches a drunken Prudence and says: “She is ill!” However, Prudence isn’t concerned, and tells him that: “She is always ill. Just when we are enjoying ourselves on comes that cough and our fun is spoiled!”

Feeling forced to act, Armand enters her sanctuary, and moves towards her once inside. It’s here, while outside the others distract the irate Count, by playing Blind Man’s Buff with him, that we have some of the most important exchanges between to two. Armand entreats her to allow him to call for help. Camille begs to differ. And warns him about who and what she is. Telling him to: “… forget that we have ever met.” At this he throws himself at her feet, saying, plaintively: “I wish I were a relative—your servant—a dog—that I might care for you—nurse you—make you well!” Again, Marguerite attempts to dissuade him, but fails. She accepts that he’s the key that unlocks the door to her prison cell.

It all reaches a terrific, dramatic peak, when Count de Varville finally breaks free from captivity, and bursts into Marguerite Gautier’s room, to discover her entwined with the young Law Student. He rages. She rages. While Armand Duval looks on, clearly pleased that she’s found the courage to break her chains, and to take control of her destiny. In a trice the partygoers – she calls them a “sponging pack” – are leaving. Allowing them to be alone together. And to enjoy a somewhat awkward embrace and kiss on which the iris this time closes.

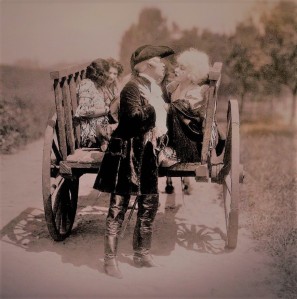

The next, middle section of the film, is simpler, less artificial and almost dreamlike. We see the happy couple in an orchard in the countryside. (It’s plain that living away from the capital is agreeing with Camille.) Armand has bought and brought to Marguerite, the gift of a book; an antique leather-bound copy of Antoine Francois Prevost’s, Manon Lescaut, a story of doomed lovers. She asks him to inscribe it for her, and then to read it out loud, which he does. Which then leads to an extended imagining of action in the novel, almost a film within a film, with Alla Nazimova as Manon Lescaut, and Rudolph Valentino as Chevalier des Grieux. Except, that the imaginings are spoiled by Camille suffering a presentiment, where she sees herself and Armand as the cursed couple.

After being joined by the newly engaged Gaston and Nichette, who perhaps present to us an alternative, less unlucky union, the action moves from Spring to Summer. Marguerite is living quietly in a conventional house – in sin or not we can’t know – and preparing to sell her belongings, in Paris, to provide sufficient funds for her future. Prudence, who’s visiting her, presents a gift of fresh Camellias with the Comte de Varville’s card inside of the box. Yet Camille isn’t impressed. And tells her to: “Take them back to Paris, Prudence! They have no place in this house!” Prudence is then unsuccessful in trying to make her see sense, and return to her old, more certain if less free existence. An existence, for all its serious restraints, that will soon be seen to be more solid and dependable, than the one which has been hastily fashioned with her Student Lawyer Amour.

The arrival of William Orlamond’s Monsieur Duval, the Father of Armand Duval, is the point at which we see the bubble pricked with a pin. In a nutshell, the Parent requests that the Courtesan relinquish her hold over his son. Telling Marguerite: that the future happiness of both his children is at stake, due to the scandal created by her becoming involved with Armand. Learning, from him, that his daughter’s imminent marriage is in jeopardy, she seeks some way out, and suggests disappearing for a while. When this isn’t found to be acceptable, she falls to her knees, to beg that Armand not be taken from her. Yet she is answered by the Father with: “There is no future for your love—you must give him up!”

I’d say, that within the confines of this drawing room, constructed at the Metro Pictures Corp. plant, for the purposes of the movie, we get a very good idea of Nazimova’s style of performing on the stage; and see, I believe, her best acting in the entire film. How she moves about simply in her plain house dress, carefree, and focused on a new life. How she deals with the irritation of the Intruder Prudence. How she expects the arrival of Armand in the automobile and hides childishly and excitedly under a blanket. How she reacts when she sees that it’s not him but his Parent. And how she battles the inevitable, and finally accepts there’s no way forward, only the way back to who she was and is. We also see fine early acting on the part of Valentino; who arrives at the residence recently abandoned by Marguerite, and discovers her note, written in on the Count’s calling card in tiny but clear handwriting. (In a nice touch their cars pass on the road in the rain.)

In Part Three of her revelatory 1930 serialization, The Truth About Rudolph Valentino, By Natacha Rambova, His Wife, Natacha explained to her readers how Rudy prepared for an emotional scene, particularly during the creation of Camille (1921). As follows:

“I remember particularly one scene in ‘Camille,’ the high point of the picture. It is where Armand, grief-stricken by Camille’s death, rushes to her apartment, where an auction is being held of all her private things. Here he sees and bids on a book he had given her years ago and which she had kept until the last.

Before doing this scene Rudy asked if he might go away by himself for a moment; then he returned and the camera started clicking. It wasn’t interrupted once. When the scene was finished tears were streaming down the face of every one of us, from director to prop boy. As for Rudy, later, I found him in a chair behind the set, head buried in his arms weeping like a child. This wasn’t make believe grief but real emotion.”

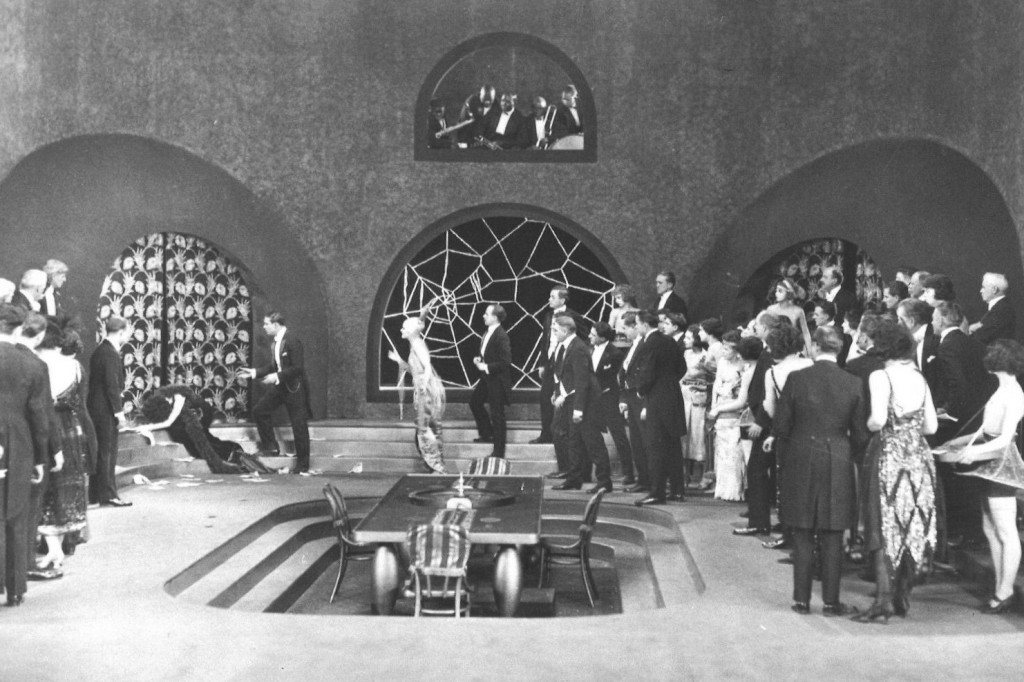

That a change is wrought in Armand Duval, is apparent immediately the camera iris expands on the Hazard d’Or; which an intertitle’s informed us, is: “… the smartest gaming place in Paris.” It’s now Autumn, and we see him gambling, immaculately dressed, his hair slicked, and with a beautiful girl on his arm. The female, named Olympe, brilliantly portrayed by Consuelo Flowerton (of the Ziegfeld Follies Spring Frolic of 1920), clings to him in a vampish manner. Another intertitle explains that she is: “… a new Daughter of Chance, whose golden beauty bade fair to rival ‘the Lady with the Camellias.'” And we believe it!

It’s here that we should pause to consider what’s certainly Natacha Rambova’s most incredible interior. The dark, light-absorbing concave room, features, again, a series of arches that draw the eye. The central arch is a performance space, or mini stage, that’s covered by a cobweb scrim, behind which exotically dressed females perform strangely. Above, is another, smaller arch, where a group of African American musicians busily play their instruments; no doubt cranking-out Jazz. And the arches to the left and right are curtained with a gorgeous semi-sheer material that features iridescent woven leaves.

It’s through the right-hand curtained archway, that the Count and Camille enter the space and pause. De Varville points out to Marguerite her former lover at the gaming table. And wickedly says to her: “Look at your broken hearted lover!” This first view of Duval for months is too much, particularly when Armand sees that she sees him, and lays his hand, sensually, on Olympe’s bared back. The close-up of Alla Nazimova is filtered and strongly lit. Yet we see her pain. And then she covers her face with her beautiful feather fan. While the Comte de Varville descends the steps into the sunken room, to place bets and gamble, she retires behind the curtain, just as she did, earlier, at her home.

Sometime after, needing a break from the table (where he’s been enjoying a serious run of luck), Armand Duval parts the curtain behind which Marguerite Gautier is resting, and gets a shock, when he sees her alone and seated there. She, in turn, is startled, as she senses a presence and turns and sees him standing. What follows now is pure Silent Era acting. And from two of the greatest screen personalities of the period. The pair must convey, without words, what they think and feel, and they do. The few words spoken are provided as intertitles. But we barely need them, so perfectly do Nazimova and Valentino express themselves with movements, gestures and facial expressions alone.

Despite toing and froing, and Armand’s desperate attempt to win her back, Camille can’t find the strength to go against her promise to his Father. When she says aloud that she promised she wouldn’t be with him, he believes her to be talking about a promise to the Count, and demands that she: “Say that you love him and I will leave Paris forever!” With deep regret and without feeling she says exactly that. He then drags her out of her hiding place and into the gaming room and denounces her. Humiliating her further by tossing his winnings in her face — a sensational moment, perhaps the most sensational in the entire picture. After a brief flicker of remorse he declares he’s through with her and with Paris and departs. Allowing the Comte de Varville to move-in, and to claim and kiss openly, and triumphantly, Olympe, Marguerite’s successor.

We’re now presented with the extended death of Alla Nazimova’s Marguerite Gautier, known also, as Camille and the Lady of the Camellias. To modern eyes, certainly to mine, this is a somewhat static, and undoubtedly indulgent section. (And for some at the time it was as well.) The passing of nearly 100 years hasn’t made Nazimova’s preferred ending – going totally against the actual written conclusion – any more sympathetic or powerful. In fact, it’s done the exact opposite. And yet, it’s what it is, and must be accepted as it is, and seen in the context of the times. (For a lot of cinemagoers it would resonate a great deal, many of them having watched loved ones die, similarly, in the recent Flu epidemic. And tears were no doubt shed in that more sentimental time.)

For ten minutes, prone, in her stylish bed, Camille approaches the end of her life. While Nanine, her faithful Servant, attempts to make that end as comfortable as she’s able. Yet, Nanine is powerless to keep at bay a group of bailiffs, who represent her creditors and have arrived to satisfy a Court Order. Thus Marguerite is subjected to a final humiliation when they arrive to look over, assess, catalogue and remove her earthly belongings, so that they can be sold to pay-off her debts. To make the interminable exit more palatable we’re given a flash-forward, rather than a flash-back, of Armand receiving from Camille a heart-felt final epistle. And, after the cruelty of the bailiffs entering her room and their attempt to take every last thing from her, including the copy of Manon Lescaut, given to her by Armand, she’s visited by a distraught but tender Gaston and Nichette, who’ve just married that day. Already in a state of delirium, The Lady of the Camellias utters some final, coherent words: “Do not weep, Gaston. The world will lose nothing. I was a useless ornament—a plaything—a momentary aurora.” Surrounded by the pair of newlyweds and Nanine she then expires; while gently calling out the name of Armand, and seeing himself and herself as they were during their affair.

It was, perhaps, the review in the September 24th, 1921 edition, of industry title, Motion Picture News, that best summed-up the starring vehicle at the time. Lawrence Reid, the reviewer, was forthright and upfront about the fact that the great Nazimova had: “… come into her own again with this modern version of Dumas’ tragedy of passion.” And had been given “a picture worthy of her expression” by June Mathis. An adaptation that was: “… intact except for the final ending.” Reid believed this to be a flaw and said so. In his review, he wonders about the reason; if it was “the shadow of censorship”, or maybe “recourse to a happier ending”, not knowing that it was, in fact, a conscious decision on the part of the Star, to diminish the impact of her co-Star and make herself the centre of attention. (Something others in the business heard of and communicated.) Yet, despite his powerful and moving performance being edited out, Lawrence Reid saw that Rudy had acted his heart out — and said so. As follows: “She is forced, however, to share honors in many of the scenes, with Rudolph Valentino, who demonstrates that the art he flashed in ‘The Four Horsemen’ was not a thing of the moment. He makes Armand a brooding, silent volcano of love who suppresses his desires until the supreme moment. His restraint is highly commendable.” (Watching it through it’s hard to argue.)

I fail to agree with the assessment, in Episode Six of Hollywood (1980), that: “The most impressive thing about Camille was its sets.” Impressive though they most definitely were, and highly talented and ahead-of-her-time Rambova absolutely was, there’s so very much more to the production. Noteworthy, alone-and-by-itself, is the fact that this was a realization driven along by three ambitious women, and in a period when very few females were able to steer anything at all in the film-making sphere. The acting of both Nazimova and Valentino, is, at many points, as already detailed, superb, and very representative of the skill of performing in a silent super feature at that time. And the supporting players – Rex Cherryman, Zeffie Tilbury, William Orlamond, and Consuelo Flowerton, particularly – are exemplary in my opinion. Of course it’s a period piece. Of course it’s not the greatest of the great silents. Of course it lacks not only the original tinting but also its original music. And yet it stands the test of time. Still entertains. Still moves us and makes us marvel. What bland, derivative, churned-out contemporary creations are going to be able to do that a century from now? Very few!

First of all I want to thank you for reading this 5,000 word post through from start to finish. I hope that it’s been as enjoyable to read as it was to research and write. This contribution, to the April 3rd to 5th, 2020 Classic Literature On Film Blogathon, will be followed by another diversionary piece, before I return, in May, to Jean Acker. I hope you’ll join me for that, later in the month, and I urge you, in the meantime, to check-out the other contributors to this marvellous exercise, at Silver Screen Classics, here: https://silverscreenclassicsblog.wordpress.com/

Thank you for this, Simon! So much of this I had never known, particularly the reviews about the sets (how one felt the competed with the actors). I’d never known, either, that—in the background—many DID think that Nazimova had deliberately cut Valentino from the ending for fear of his stealing her thunder. I know so many feel that now, but never realized reviewers at the time felt the same. Reading this makes me want to watch “Camille” again! Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The word went out, over time, that Alla had cut him out — Hollywood’s always been a small town and was even more so in those far-off days. I’d like actually to see a copy of the script, as I noticed, from promotional images, that Tilbury’s character, Prudence, visits Camille when she’s dying. So that’s three major cuts that I know of now. I don’t doubt there were more. (Maybe from the Manon Lescaut sequence.) I do hope you watch it again. Be great to hear from you once more afterwards! Stay safe!

LikeLike

Camille is not a story that I return to often, thinking it is not something that touches me. Yet I read this review with great interest and memories and music flooded my thoughts. I look forward to seeing and reveling in this story soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Then my time wasn’t wasted! Thanks for reading and for commenting!

LikeLike

Thanks for this in-depth look at a pivotal moment in the careers of two stars. From the near disastrous audition to the subsequent mistreatment of the up-and-coming star (via the film’s editing), there was apparently as much drama behind the scenes as in front of the camera. A real-life, silent era version of A Star is Born.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A pivotal moment indeed — one Star rising and one Star falling. Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLike

I’ve not seen this version, but I need to rectify that ASAP. It sounds marvellous – the wardrobe, the sets, and especially the cast.

Your review is like reading an essay included in a Criterion blu-ray. Very informative and full of interesting research. When I finally do see this version, I’ll be back to re-read your thoughts and compare notes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can’t wait! And thanks, again, for including me in the Blogathon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent review! Detailed and very informative. Anyhow, I really liked this modern adaptation of Camille! Nazimova and Valentino were an interesting screen couple. And I’m glad you mentioned the sets… they were fantastic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you — “an interesting screen couple” indeed. 1921 was a great year for Rudy, with no less than five films, and two of them HUGE hits. Superstardom was just weeks away when Camille was premiered in New York. And we’re still talking about him a century later!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The original ending is what Nazimova used….Armand was NOT there….Project Gutenberg has the book for free…

The final end was in a series of letters to Armand, recounting her death….For example:

“…After this the few characters traced by Marguerite were indecipherable, and what followed was written by Julie Duprat.

February 18.

MONSIEUR ARMAND:

Since the day that Marguerite insisted on going to the theatre she has got worse and worse. She has completely lost her voice, and now the use of her limbs.

What our poor friend suffers is impossible to say. I am not used to emotions of this kind, and I am in a state of constant fright.

How I wish you were here! She is almost always delirious; but delirious or lucid, it is always your name that she pronounces, when she can speak a word.

The doctor tells me that she is not here for long. Since she got so ill the old duke has not returned. He told the doctor that the sight was too much for him.”

MORE

While June Mathis may have changed the ending and Nazimova cut it….the fact is Armand wasn’t there i the original work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How nice of you to take the time to point that out! Appreciated! Thanks!

LikeLike