His Fame Still Lives is looking at Rudolph Valentino’s final complete year on Earth on an almost daily basis. Not surprisingly, this involves consideration of the three productions: two made and one unmade. The first to reach fruition, Cobra (1925), in the midst of creation a century ago this month, is here compared with the source material: a play by Martin Brown, which enjoyed some success, in both 1924 and 1925. In order to understand better the actual movie I’m investigating what inspired it. So here’s that investigation, titled, as you can see: The Original Cobra.

The earliest mention His Fame can find of Cobra the play, is in the Thursday, January 3rd, 1924 issue of VARIETY. On page 146, under an attention-grabbing half page ad. for Mabel Normand’s latest picture, The Extra Girl (1923), we see an announcement by L. Lawrence Weber, Producer, concerning his current and upcoming attractions; which, in order, were: Little Jessie James at the Longacre Theatre, Moonlight at the Little Theatre, and Oh Baby, “A New Musical Comedy”, and Cobra, “A Drama”. According to TRAVELANCHE, L. Lawrence Weber (1869-1940), was a myriad of things, with interests, over the years, in: minstrelsy, burlesque and vaudeville, boxing, theatre, the film-industry and more. (Possibly he crossed paths with Valentino at some point as a result.) As the owner, in the early Twenties, of both the Longacre and Little theatres, he was in a position to present what he chose to, which is exactly what he did.

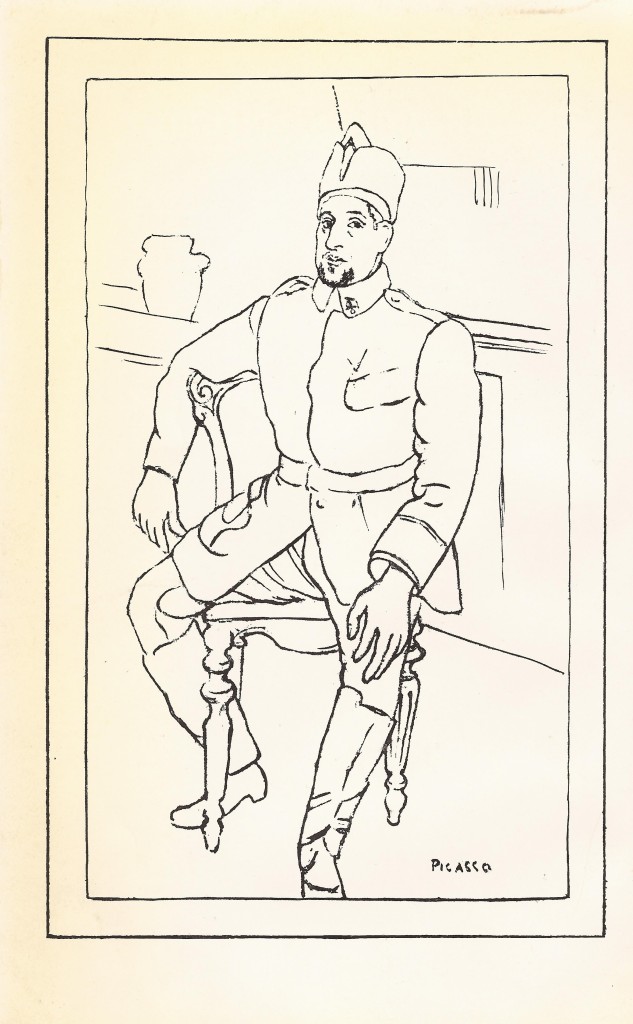

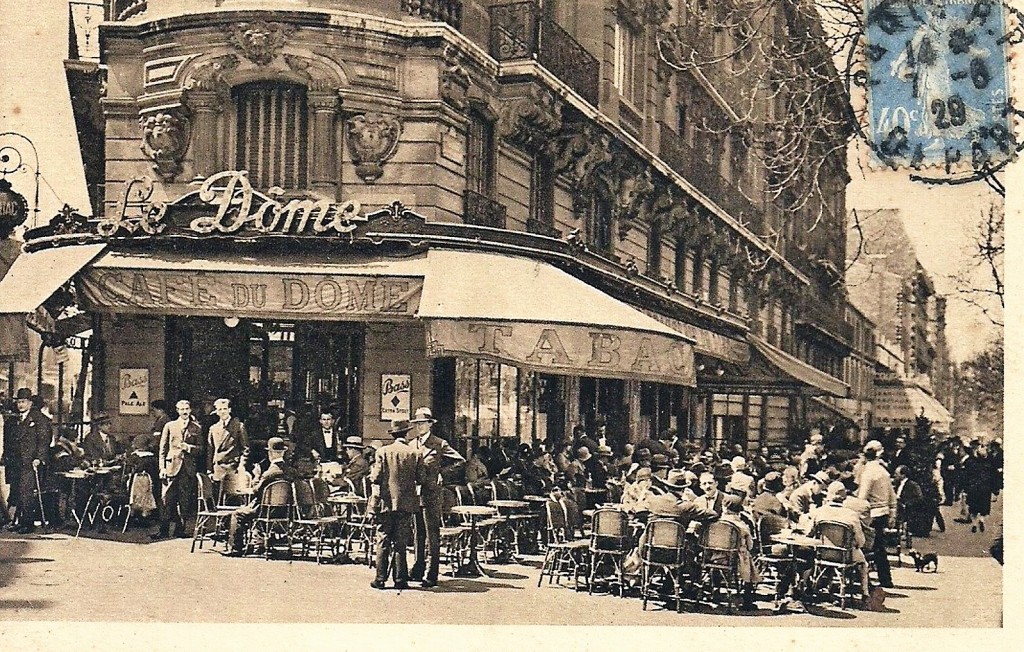

Martin Brown (1884-1936), who wrote Cobra, enjoyed a career almost as varied as his Producer. A series of obituaries and promotional pieces, reveal he was born in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, which is presumably where he dropped out of college and entered a drama school. THE BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE tells us that between 1907 and 1914: “… he appeared in many plays and musical comedies…” until a weak heart forced him to give up this profession. This year seems unlikely, as His Fame found an image of him, in the November, 1915, issue of MOTION PICTURE MAGAZINE, with [Roszicka Dolly], one half of the famous Dolly Sisters, where he is credited, with her, as being a Dancer. (The fact they were an act in 1913, which he then returned to when WW1 broke out in Europe, is of interest, because it is before Rudy became an Exhibition Dancer.) And an announcement in The Billboard proves he was still in Show Business in early 1916.

Weak heart aside, whenever he began to write, he appears to have begun to get somewhere by 1917; which is when William S. Hart used his story, written with Lambert Hillyer, as the basis for a motion picture he not only starred in but also directed, titled: The Desert Man (1917). This was followed, in 1918, by his three act play, A Very Good Man, being adapted for Bryant Washburn, for a film with the same title. After a dancing comeback – MARTIN BROWN’S COMEBACK, VARIETY – that same year, his play The Prodigious Son, formerly You Wouldn’t Believe It, was put into production by Charles Hopkins. (Hopkins having previously produced A Very Good Man).

In the September 1919 edition of SHADOWLAND, he was featured alongside his contemporaries, now also largely forgotten, in an article over a couple of pages, entitled: Where the New Stage Playwrights Come From. The following year, A Double Bar, was purchased by the Selywns. And another effort, An Innocent Idea, was presented by Charles Emmerson Cook and staged by Max Figman, at the Fulton Theatre. (An acid review in The Billboard, on June 12th, detailed his time as “vaudeville buck dancer”, or, a Performer: “… who went in for the shirtless, pantsless school of Terpsichore…”, the Author refused to be totally sure.) Late in 1922, his play that year, The Exciters, was adapted for the screen by Julia Crawford Ivers. The adaptation, starring friend of Rudolph Valentino Bebe Daniels, was produced by his then Employer Famous Players-Lasky. The motion picture, also named The Exciters, was released in 1923.

VARIETY‘s review of Cobra, in their April 30th, 1924, edition, lavished praise on Martin, stating he was a person with: “… a flair for dramatics.” (This review further reveals that Cobra had been preceded by a modestly successful drama titled The Lady.) His Fame also discovered he was a person who considered himself extremely unlucky – detained after arriving from France, the loss of his baggage, near drowning, burglary and theft, and a serious hand injury – due to the series of five flops he endured before success, in 1924; a jinx he blamed on his work being consistently altered by producers. (Which is exactly what would happen to Cobra.) Fast forwarding, we see he was later contracted to both Paramount and Universal. The ad. for employment with the former, as can be seen above, listing twelve plays up to that year — 1930. Half a decade later, in 1936, he passed away at the age of 51; succumbing, according to his Sister, with whom he lived in New York, to Bronchial Pneumonia at Bellevue Hospital. He was further connected to Valentino by the fact that his funeral was handled by Campbell’s. The service being held at the Campbell Funeral Church, at noon, on February 15th.

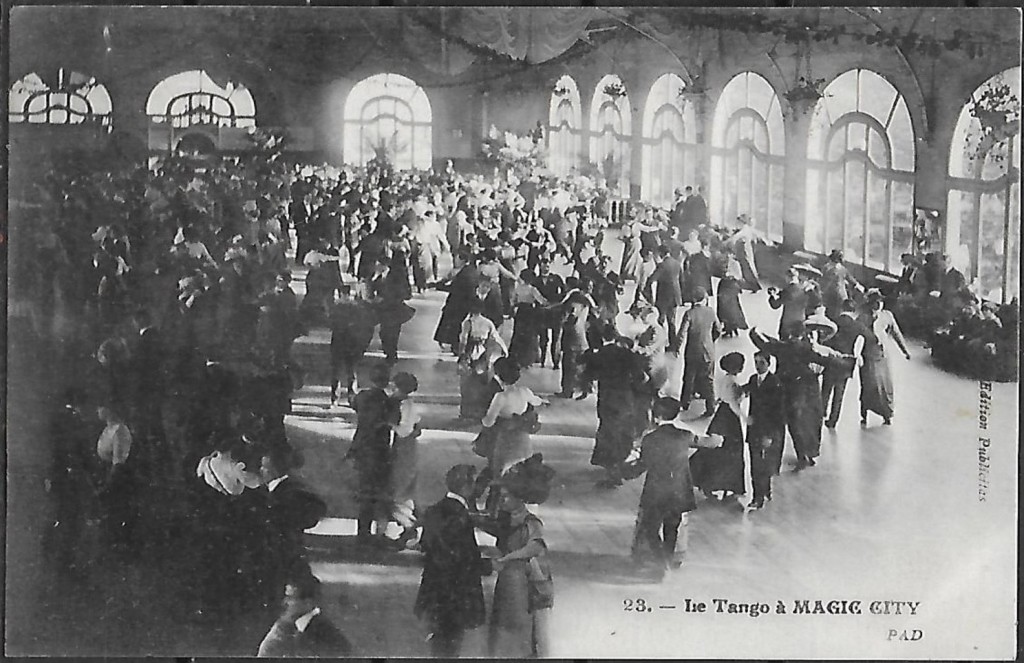

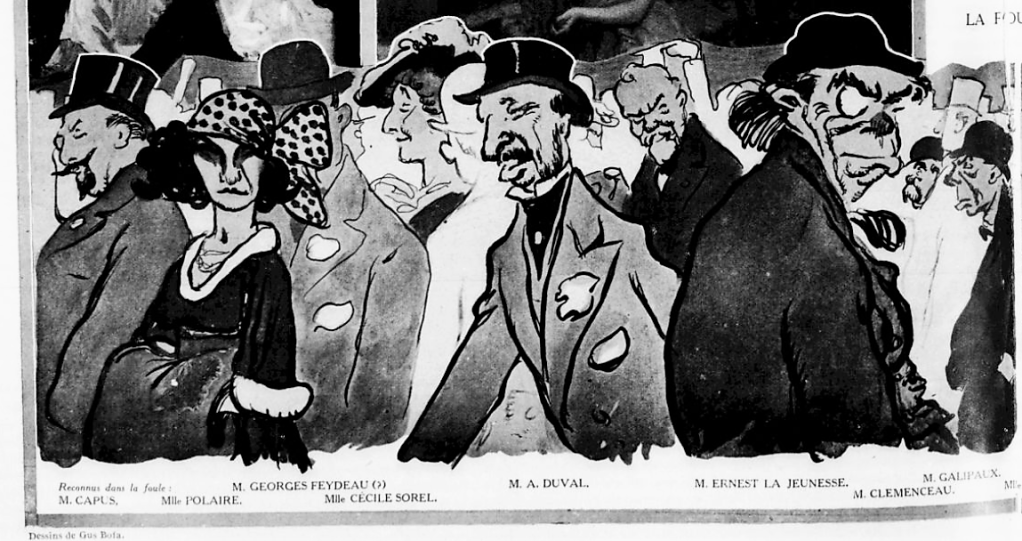

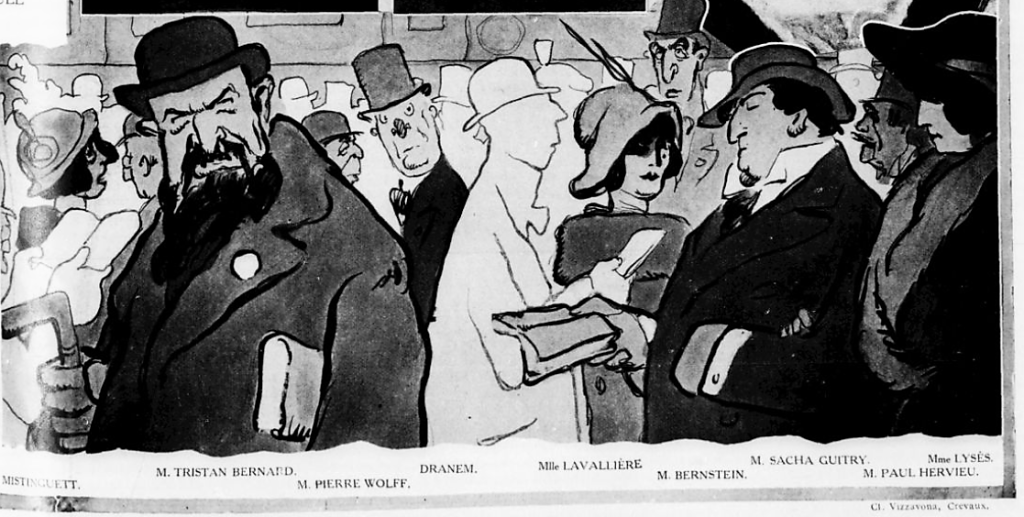

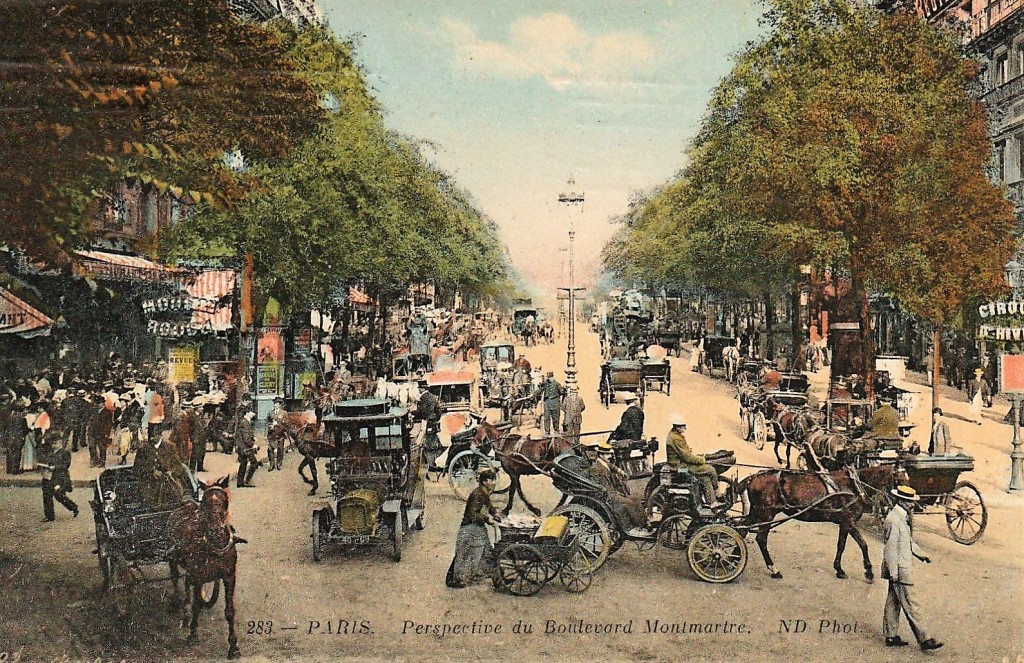

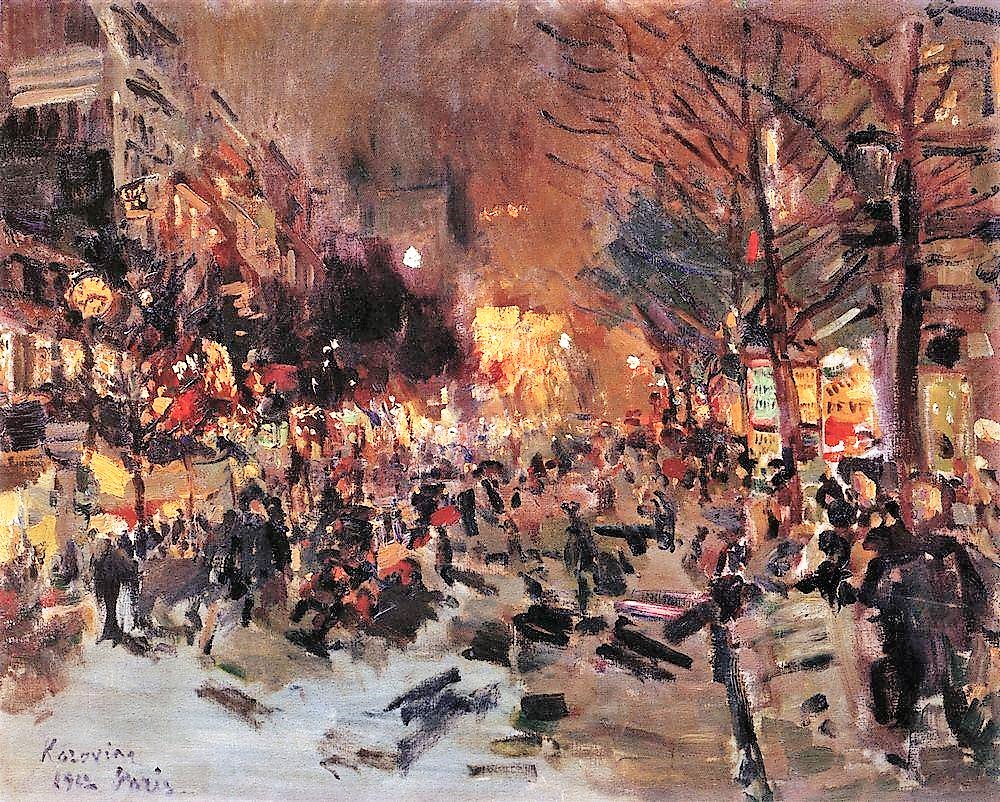

Cobra opened, April 22, 1924, at the Hudson Theatre, an already important establishment which is still in operation today. The cast being as follows: Sophie Binner as Dorothy Peterson, Louis Calhern as Jack Race, Ralph Morgan as Tony Dorning, Judith Anderson as Elise Van Zile, Clara Moores as Judith Drake and William B. Mack as Resner. VARIETY‘s review begins by explaining it was Weber’s third production that year and was “a sharp change of pace” following the two musical comedies advertised three months before. Would Cobra have a successful run after opening late in the Season and having to compete with the Democratic National Convention? It was hard to say. (Cobra would total 63 performances, between April and June, according to IBDB, the Internet Broadway Database.) The play’s title, the Reviewer states, encapsulates a certain type of female who can entice “the strongest of men”. Was there some plagiarism? Similarities existed, the Writer felt, to a play titled “Any Night”, which also featured a lethal hotel fire. The difference being, that in Cobra the fire happens off-stage; though, it was clearly based on an actual fire, at a disreputable Fifth Avenue property where the victims were burned beyond recognition.

The opening scene of the four act play is set in the shared accommodation of two college men. Jack Race an athletic Ladies Man. And Tony Dorning a less so Wealthy Weed. The two are best friends, to the point that Race is given much needed assistance when blackmailed by one of his feminine acquaintances, Dorothy Peterson. Not too much later, they are visited by The Cobra of the title, Elise Van Zile, who pretends to be “demure”. Elise: “… makes all manner of fuss over the strapping Jack, but turns her wiles on Tony when she learns he is wealthy…” Tony Dorning then marries Elise Van Zile and is still happily married four year later. However, he is unaware that all through their seemingly blissful marriage, his Wife has been attempting to seduce his Friend and Work Partner.

Finally, while Mr. Dorning is out of Town on a work trip, Mrs. Dorning manages to lure Mr. Race. They have dinner in a private room at a hotel she recommends. However, Jack manages to tear: “… himself away from the vampish wife.” Staying behind following his dramatic departure she is caught up in the conflagration and dies. When he returns, Jack’s Friend Tony find’s that Elise is missing. Only Jack and Jack’s Secretary, Judith Drake, know the truth. (Jack has confessed what he knows to Judith.) Tony finds out the hard way, when he opens letters his vanished Spouse wrote that mention the hotel that was engulfed by fire.

VARIETY’s Reviewer felt Judith Anderson’s portrayal of Elise Van Zile was exemplary. And that she was the stand-out Performer. Going so far as to state: “… there are few actresses who could have played the role better.” Anderson apparently delivered several lines with great skill. For example: “In breaking down the self-respect and moral determination of her husband’s best friend she declares: ‘You’ll be taking nothing from Tony.’ In smoothing the way to the rendezvous she adds: ‘there can be no trace,’ and when he counters: ‘except in our souls,’ she parries: ‘Suppose we have none; suppose this life is all.'” Ralph Morgan, who played Tony, was “splendid”. Louis Calhern, as Jack, though “stern”, was suited to the role. Clara Moores, playing the Secretary, Judith Drake, did not receive an opportunity for “vivacity”. William B. Mack, as the “wronged businessman” Rosner”, failed to project sufficiently. And Dorothy Peterson, who appeared only in Act One, as “‘a damned little tart'”, was given no praise or criticism. The Reviewer found the two “settings” – dorm. and office – to be “well-designed”. Felt that the six-person production should be profitable. And, lastly and most importantly, believed the following: “As a picture story it ought to draw a good price, particularly if the play accomplishes a successful engagement on Broadway.”

Not fully satisfied with the description of Cobra in the review, I searched around for a more complete example and was very lucky to find one, in the Sunday, July 6th, 1925, edition of THE DAILY OKLAHOMAN, Section D, Pages 5, 6 and 8. This was, the news titled explained up front, “The Year’s Best Plays in A Flash” and: “… the tenth of a series of short stories made from the latest New York theatrical hits.” So what I had managed to find was a nicely condensed version of the actual play as enjoyed by theatre-goers that year. And thanks to this, I was able to see what had been added and deducted in the process of bringing Brown’s Cobra to the Silver Sheet — which, as you’ll see in the following summarisation, was a great deal.

ACT ONE

Jack Race, a virile Athlete, admits that he falls for every Flapper that crosses his path.

Tony Dorning, delicate and artistic and his Harvard Room Mate, always has to rescue him.

They’re sincere friends despite their differences.

Jack, actual name Jonathan, reminds Tony, obviously Anthony, of a white bull he once saw confronted by a Cobra in India. Despite the ability to crush the serpent the impressive bovine got bitten.

Jack understands the story and sees his Friend’s point.

Here Elise Van Zile makes her entrance. Golden-haired, blued eyed and about twenty, she pretends her Aunt, her Chaperone, was due to join them. Obviously this isn’t the case. “Coy, mysterious, ecstatic by turns” she make Jack a nervous wreck.

Jack tells Elise about Tony and his family being Fifth Avenue art dealers.

Tony arrives and is smitten with the now less forward girl and takes her home in his car.

ACT TWO

Jack, working at Dorning’s on Fifth Avenue in New York, is single and troubled.

Tony suggests to him his Secretary, Judith. (Judith is tallish and not a beauty yet does have qualities.) Elise, his Wife, isn’t enthusiastic. And interferes by warning Judith off.

Miss Drake says that she plans to leave her employment anyway, but tells Mrs. Dorning that Mr. Race hasn’t done anything improper.

With Tony planning to be out of Town Elise suggests her Husband ask Jack to take her to dinner and to the theatre. Jack says that he is unable to which upsets Tony. Jack then admits to being in love with his Secretary, Judith.

Suddenly, without warning, a man walks into the room through the door. His name is Rosner and he claims that Dorning has ruined him in business. He then pulls a gun from his pocket and aims unsteadily. Race pushes Dorning behind him then walks calmly towards Rosner. And as the clearly nervous Rosner falters he takes the weapon from his shaking hand. Tony Dorning is by the table speechless. After talking the assailant understands that he was wrong to think Mr. Dorning has tried to ruin his life and eventually Rosner leaves.

Judith then enters the office and Jack takes her to the side and tells her he loves her. However, his Secretary tells him that she’s sorry, but they can never be a couple, for two reasons: “one, he wouldn’t understand; and the other, he wouldn’t believe.” This all puzzles Jack. Judith leaves.

The door opens and Elise enters dressed in black. Jack asks her why she has returned to Dorning’s. The reason, she says, is she wishes to speak with him alone and then maybe go to dinner. Jack declines her offer prompting his Friend’s Wife to tell him that she only married Tony for his money and the lifestyle she could consequently enjoy. Tony loves her but she doesn’t love him. She wants Jack and always has done.

Jack then tells Elise that he’s going to Africa on a scientific expedition. To which Elsie responds that he is running away.

Elise then brings up Judith, Miss Drake, and Jack asks her what she has to do with her and him. Elise tells him that she warned Judith off.

When Jack tells Elise that he was planning to propose marriage to Judith Elise tells him that Miss Drake told her he wasn’t her type.

“The cobra had struck…”

Jack thinks that Judith was unable to tell him she couldn’t love him in return.

Jack says he is no longer a man who sleeps around and he is through with that sort of life.

Elise dares him to say that with her in his arms.

He reveals that he could hold her and kiss her but never love her due to her being his Best Friend’s Wife. He then reminds her of the letter that she wrote to him a year ago. And he tells her it would hurt Tony if Tony knew.

Elise tells him to never show it to Tony. She also tells him his cruel reply is locked up and is tear-stained. His cruel words meant more to him than the loving words of others.

Tony feels himself under her spell.

Elise suggests they go to dine at a hotel, just the two of them, and then he can leave her there and go to a Philadelphia appointment.

ACT THREE

At the office the following day Jack sees Judith — she looks tired.

Tony Dorning has stepped out and has asked Jack Race to wait.

Miss Drake tells Mr. Race that Mr. Dorning is worried. When Jack asks what about Judith tells him that Tony’s manner is strange. She stops in the doorway and tells him she is sorry about how she responded to him the previous day.

Jack says he has been thinking too.

He will go away alone as he now realizes he is not good enough for her.

Judith then reveals to him that one of her two reasons why it would not work between them was that she wanted him to take her away.

Jack asks if the other reason is Elise.

Judith replies that she never asked for Mrs. Dorning’s help and that Elise Dorning had lied to Jack about that. Miss Drake then tells Mr. Race that Mrs. Dorning is as clever as she seems.

Before they can speak any further Tony enters the room. His Wife, Elise, is missing.

Tony takes up Jack’s suggestion that Elise might be at her Aunt’s. He leaves.

When he’s gone Jack Race sees in the newspaper that the Van Cleve Hotel has burned down. Burying his face in his jacket sleeve he accidentally presses a buzzer which summons Judith Drake.

He confesses that he took Elise to the hotel last night.

Miss Drake is horrified.

Jack tells Judith he can never tell Tony but she feels he should.

The phone rings and Jack answers. Tony tells him that Elsie is not at her Aunt’s.

ACT FOUR

A whole year has passed. Jack continues to work at Dorning’s but has visibly aged due to the secret.

Rosner, the man who tried to kill Dorning, brings in papers and they talk. Race wants Rosner’s advice. Should he go to Dorning who has locked himself in his Wife’s room?

It was a year ago four days ago that she vanished.

Rosner advises him to go, yet, as he prepares to leave the phone rings and he answers it.

Judith Drake is there to see him. He asks that she be shown in.

She has been in the West for twelve months. She regrets calling him a Coward.

Suddenly Tony appears in the doorway. He tells them both he has something to say — that he knows Elise is dead and also where and how she died. While clearing out her belongings, untouched since her disappearance, he found letters in her desk. He knows the truth.

Two months ago he received an anonymous note asking if he had tried to get the remains at the burned hotel identified. After this he found Jack’s letter to Elise. He then tells Judith how Jack saved his life when Rosner tried to shoot him. So Jack has saved him twice.

Mr Dorning tells Miss Drake she should accept the love of Mr. Race.

Judith’s eyes fill with tears and she reaches out her hand to Jack who takes it in his while Tony watches them both.

Tony Dorning appears to have the last line:

“We need never speak of this again,” he added quietly, “we will–just go forward–now–together.”

The End.

If you have read the condensed play through you will have seen how very different it is to the film based on it. The Opening Act is in the friend’s dorm. They don’t meet at a fictional European resort. They are students and have known one another other for some time in the United States. Jack Race, played by Rudolph Valentino in Cobra (1925), is an American Athlete, not an Italian Count. Tony Dorning, Casson Ferguson’s role, name-changed, for some odd reason to Jack Dorning, is an American Toff and, later, an Art Dealer not an Antique Dealer. In Act One, we encounter both the “damned little Tart portrayed so well by Eileen Percy in the motion picture, and Elise Van Zile, future Mrs. Dorning, who is the Cobra of the title. It is a bit of a surprise to learn that in the original story Elise is a blonde with blue eyes and not dark-haired and dark-eyed like Nita Naldi. (Here before us are the ingredients!) There is no problem with a local girl as we see in the film. There is no flashback sequence to an ancestor. There is no journey on a Liner to the USA from the Continent.

Act Two is sometime in the future. Jack is already working at Dorning’s, whereas, in the screen adaptation, he joins the concern after arriving in New York. Jack’s Friend, Tony, suggests that he try his luck with Judith his Secretary, and this is objected to by Elise. In the film we instead see Rodrigo, Valentino, chatting to her and indicating without much subtlety that he likes her a lot. We do not see Mrs. Dorning yet. In fact she has not even met or married Mr. Dorning. As Miss Van Zile she will be seen in the movie at a nightclub with her Aunt and Uncle. And it is there that she becomes acquainted with Rudy’s Count. Also later, is the discovery, by Elise, that the Count has little finance and few prospects. This all happens at Afternoon Tea; which already happened in Act One of the play. In the rest of Act Two, Mrs. Dorning warns off Miss Drake; Miss Drake tells her she will leave her job soon but that Mr. Race has done nothing untoward; before leaving Elise Dorning asks her Husband to ask Jack to take her out while he is out of Town; Jack declines and tells Tony he is in love with Judith. The appearance of Resner, which is unexpected and alarming, seems to have been transformed into the fight with the man at the nightclub. However, it lacks the punch – intended pun – of the threat on Tony Dorning’s life, which shows us the level of Jack Race’s selflessness. On the screen, instead of protecting Dorning, Torriani protects himself. The stage version has Judith telling Jack that she cannot love him back or be with him. Then we encounter again Elise, dressed provocatively, who, in the absence of Tony, manages to entice Jack to a certain hotel.

Act Three, centred on the following day, is a fairly simple scene that is actually included in the film pretty much unchanged. Jack is at the office and has a discussion with Judith. This talk is about the two of them and they are very honest with each other. However, their frank exchange is interrupted by the arrival of Tony, who is extremely worried, because his Wife did not return home the night before. Jack tries to assist his Friend suggesting she may be at her Aunt’s. When he leaves Race notices the newspaper, where he reads that the hotel they went to has burned to the ground. He is distraught. Drake enters and he tells her he knows what happened but that he can never tell Dorning.

Act Four concludes the play quite nicely. Jack Race continues to work at Dorning’s, yet he has aged badly, burdened as he is with guilt. It is a year and four days since the disappearance of Elise Dorning and Tony Dorning, consequently, hasn’t been seen for quite some time. Resner, working now at Dorning’s, when asked by Race, feels Race should go to see his Friend. Judith then appears. Having left her position as Secretary, as she told Elise she would, she has returned to New York and dropped in to say hello. Miss Drake tells Mr. Race she regrets the things she said including calling him a Coward. Mr. Dorning again interrupts to say he knows all about Mrs. Dorning’s disappearance and death. And, basically, that life is short, and both Jack and Judith should recognize that they love one another and become a couple. The ending, after all of the tragedy, is rightly a happy one.

In conclusion I would just say that I am amazed they tinkered with the source material to the extent they did. Who is to blame, due to the later blame game, is uncertain. J. D.? S. George Ullman? Rambova? Anthony Coldewey? Rudy himself? A combination? Ultimately we shall never know. However, because of the previous ruining of A Rope’s End, the source for A Sainted Devil (1924), the finger of suspicion points firmly at F. P.-L./Paramount. The jinxed Martin Brown’s play is a tight and understandable story where the characters have natural motivations. This is not the case in the screen adaptation, which, literally, takes us to territory it does not need to. Compared with Brown’s original the motion picture is untidy. The comedy does not sit well with the tragedy. And Naldi’s reprise of her serpent-like performance in Blood and Sand (1922), is really just more of the same old same old, in the opinion of His Fame. The ending, perhaps the oddest alteration of them all, is flatter than a pancake. And yet, despite all of this, Rudy is a redeeming factor. It’s hard to fault his performance. He moves with his usual grace and assurance through the mess in which he finds himself. Lifting the production to a height it would never have achieved without him. And thank heavens for that!

I want to thank all those who have taken the time to read this in-depth look at Martin Brown’s original play and how it contrasts with Cobra (1925). I hope you enjoyed it as much as I enjoyed putting it together over the past fortnight. As previously, with 1923, His Fame is looking through a powerful eyeglass at 1925. As it is only mid. February there is much to be uncovered and posted at Facebook and on YouTube. I look forward to that, and, to your thoughts/comments if you have any. Take care!